Positional exchange and positional changes in consonant sounds of the Russian language. Positional vowel change

Phonetic processes in the field of vowels .

Positional exchange. The main cases of positional vowel exchange include cases of qualitative reduction of vowels A, O, E in unstressed positions. Qualitative reduction- this is a weakening of the sound, which is accompanied by a change in acoustic-articulation characteristics (the sound changes its DP). There are positions: percussion– the sound remains unchanged (strong position); first pre-shock- the first degree of reduction; second(all other unstressed positions) - the second degree of reduction (weak first and second positions). The sounds I, U, S do not undergo qualitative changes, they change only quantitatively. The qualitative reduction of these sounds has different results, depending on whether they are after a soft or hard consonant. See table.

Let's not forget the manifestation of the absolute beginning of the word, where A and O both in the first and second positions will be the same / \ (instead of / \ for the first and expected b for the second position: ORANGE. E, respectively, in the first and second positions will be ( instead of in the first and b in the second): ETAJERKA [t/\zh'erk].

*Sometimes after hard hissing F, W, C in the first position A instead of the expected / \ sounds like E: you just need to remember such words - JACKET, Pity, Pity, SORRY, SORRY, RYE, JASMINE, HORSES, TWENTY, THIRTY. But this is no longer for me, but for the next topic (changes), and also for orthoepy.

positional changes. Positional changes include the phenomena accommodation vowels before soft and after soft consonants. Accommodation is the process of mutual adaptation of sounds of different nature (a vowel to a consonant or vice versa). After a soft consonant, a non-front row vowel moves forward and upward in education at the beginning of pronunciation (progressive accommodation), before soft - at the end (regressive accommodation), between soft - throughout pronunciation (progressive-regressive accommodation).

For sounds O, A, E - only under stress - all 4 cases are possible; for sounds U - and under stress, and no all 4 cases; for Ы and under stress and without stress, only 2 cases of Ы and Ыя are possible; Sometimes instead of Yo (between soft ones) they denote k - SING [p’kt ’]. Y and J are considered soft.

Another case of positional changes is the progressive accommodation of the initial AND in Ы, when a consonant prefix is added to the root: GAME - TO PLAY (this applies to changes, as it knows exceptions - PEDAGOGICAL INSTITUTE may also pronounce AND).

Non-phonetic processes in the region of vowels.

at the root - BIR//BER, GOR//GAR, disagreement//full agreement, E//O, A//I, U//Yu at the beginning of the word, O//E of the SPRING//SPRING type; in the prefix - PRE / / PRI, NOT / / NI, in the suffix - EC / / IK, EC / / IC, OVA / / EVA / / YVA / / IVA, IN / / EN / / AN, in adjectives; at the end - OV / / EV, OY / / HER, OH / / HER, OM / / EM, TH / / OH / / EY

2) Historical phoneme alternations with zero sound (“fluent vowels): at the root - DAY / / DAY, WINDOW / / WINDOWS, COLLECT / / TAKE, WHO / / WHOM, WHAT / / WHAT, in the prefix - THROUGH / / THROUGH, PRE / / PERE, C / / CO, VZ / / WHO , V//VO, OVER//NECESSARY, FROM//OTO, KOY//KOE, in the suffix - PEAS//PEA, RED//RED, BIRD//BIRD, TI//T verbs, SK//ESK, SN//ESN in adjectives, at the end - OY//OYU, in the postfix - СЯ//СЫ

The alternation ONE//ROZ refers to phonetic types of spelling and is one of the rare cases of reflection in writing of not historical, but phonetic alternation within the same phoneme - a strong position O (under stress, which naturally sounds in the first and second positions, respectively, as /\ and Kommersant, which is reflected in the letter as A.

Phonetic processes in the field of consonants.

Positional exchange. The positional less consonants include diverse processes, united by a common feature - they do not know exceptions. 1) Positional stunning of noisy voiced at the end of a word - GENUS - GENUS [T]; 2) Regressive assimilation by voicing - noisy deaf voiced before voiced MOW-KOSBA [Z] (assimilation is the process of assimilation of homogeneous sounds - the influence of vowels on vowels, consonants on consonants, in contrast to accommodation); regressive assimilation in deafness - noisy voiced ones are deafened before noisy deaf ones - BOAT [T]. The process does not concern the sonorants - neither the sonorants themselves, nor the noisy ones before the sonorants. The double role of sound B is interesting (it is not by chance that some also consider it sonorous). In front of him, the noisy ones behave not as in front of a voiced, but as in front of a sonorous voice - they do not sound out (TAST: T does not turn into D); and he himself behaves like a noisy voiced - in front of a deaf person and at the end of the word is deafened - SHOP [F]; 3) Regressive assimilation in softness - will be a change only for the anterior lingual dental D, T, C, Z, N in front of any of them soft: VEST [S’T’]; 4) Complete (such assimilation, in which the sound changes not only one DP, but completely its entire characteristic) regressive assimilation Z, S before hissing Sh, Zh, Ch, Shch, C - SHUT [SHSH], HAPPINESS [SH'SH'] ; T and D before H - REPORT [H'H']; T + S \u003d C - FIGHT [CC]; T and D before C (FATHER [CC]; C and Z before SC (SPILL [SH'SH ']; 5) Dieresis (loss of sound on a dissimilative basis) - KNOWN, HOLIDAY; 6) Dissimilation (reverse assimilation - dissimilarity of sounds) G before K - SOFT [HK]; 7) Accommodation in softness before I, b, (except C, W, F, H) - HAND / / HANDS [K] / / [K ']; 8) Vocalization of the phoneme J: as a consonant sound j appears only at the beginning of a stressed syllable (YUG), and in other positions it acts as an AND non-syllable - a vowel sound.

Note: At the end of participial and participle suffixes does not go into F; there is F, because in a strong position it never sounds like B (there is no alternation). The same thing - it is necessary to distinguish, say, the loss of sound in synchrony SUN and in diachrony FEELING, where at the modern level there is no loss, because. there is no alternation with its full variant.

positional changes. Processes that occur as a trend, but with exceptions. 1) Assimilation in terms of softness of the lips and teeth before the lips and R before the lips (BEAST, LOVE). The old norm required just such a pronunciation, but now, apparently, under the influence of spelling, this is not relevant. 2) Assimilation by softness before j: most often it softens, but, again under the influence of spelling, before the dividing b, denoting j at the junction of the prefix and the root - a solid consonant SEAT [C] sounds; 3) Irregular dissimilation of H before T or H: WHAT, OF COURSE [PC] [SHN] (does not always happen - for example, SOMETHING - already only [TH]); 4) Accommodation in the softness of hard before E - now, in many foreign words, it is also possible to firmly pronounce the consonant before E: REVENGE [M '], but TEMP [T]. 5) Stunning of a sonor in position at the end of a word after a hard PETER. 6) Vocalization of a sonor - the acquisition by a sonorant consonant of a syllabic character in a cluster of consonants - SHIP [b] L, TEMB [b] R. All of these processes are also orthoepic at the same time, because fluctuations in regular pronunciation - this is the reason for orthoepic variation.

Non-phonetic processes in the field of consonants.

1) Historical alternations of phonemes: traces of palatalizations (first, second, third) HAND//HAND; traces of influence of iota LIGHT//CANDLE; traces of simplification of consonant groups BEREGU//BERECH; stun at the end of a word (unchecked DO [F]); the historical change of Г to В in the endings of adjectives - RED [В]; alternation of suffixes CHIK//SHIK; non-phonetic (phonemic) softness - I WILL // BE, ZARYA // RADIANT (here it is not softening, because in the word ZARYA before A should not be softened (non-front row) - there is no positional conditioning).

2) Historical phoneme alternations with zero sound (“fluent consonants): traces of L-epenteticum - EARTH//EARTH [–]//[L]; historical diarrhea (untested) FEELING, LADDER; adjective suffixes SK//K; the end of OB (EB) / / - (GRAM / / GRAM).

Note. The change of Z//S in prefixes like IZ, WHO, RAZ, although it is reflected in writing, is in fact not a historical, but a living, phonetic process of assimilation by voiced-deafness: it’s just that phonetic, not phonemic writing is implemented here.

Russian consonants literary language in their composition, which was defined above, they appear in a position before vowels, and before [a], [o], [y] all consonants can be used, i.e. in Russian there are combinations of all consonants with these three vowels; before [and] only soft consonants appear, and before [s] - only hard ones. As for the position before [e], it requires special consideration, since in the modern literary language it turns from a position in which there is a positional change of a hard consonant to a soft one, into a position in which all consonants can act, which is associated with the spread pronunciation of hard before [e] in loanwords and abbreviations (see details below). However, in general, it can be said that the position of consonants before vowels is such a position in which neither positional exchange occurs (with the exception of partly the position before [e]), nor positional changes of consonants.

The positional exchange of consonants in the Russian literary language is connected "first of all with the relations of deaf-voiced noisy in position in front of noisy ones. According to syntagmatic laws, in the Russian literary language in a position in front of deaf noisy voiced noisy positionally change to deaf (lu [pk] a (from lubok ), la [fk] a, dirty [tk] a, sya [t'-k] and sit down, ny [sk] o, lo [s't '] climb, lo [shk] a, but [kt '] and), and deaf noisy before voiced ones - to voiced (o [dg] give, [Zd]at, [make, [g-home]); at the absolute end of the word, only deaf noisy ones (bo [n], sy [p '], cro [f], cro [f '], su [t], xia [t '], in [s], le [s '], mu [w], to [w '], sleep [k]), i.e. there is a change of voiced to deaf.

Thus, if deaf and voiced [p] - [b], [p '] - [b '], [f] - [c], [f '] - [c *], [tі - [d], [t '] - [d'I, [s] - [s], [s '] - [s '], [w] - [g], [w '] - [w '], [k] - [g], [k '] - [g '], then in the position in front of the deaf noisy ones only [n], in '], [f], [f '], [t], [t '], [s], [s '], [w], , [k], [k '], and in the position before voiced - only [b], [b '], [c], [c '], [d], [d*], [h], Іz'], [g], [g'1, [g], [g']. At the absolute end of the word, only the same deaf ones are possible as before the deaf noisy ones, with the exception of [k '], which is absent in the modern literary language in this position.

It must be borne in mind that in the vocabulary of the Russian language and in its morphological forms there may be no formations with combinations of some deaf consonants, especially deaf soft ones, before deaf noisy ones: in some cases this absence is due to the non-proliferation of combinations of soft consonants with subsequent consonants, in others - with the accidental absence of such formations; the same applies to voiced consonants in a position before voiced noisy ones.

As a result of positional exchange in the Russian literary language, an intersecting type of positionally changing deaf-voiced noisy consonants is formed, when in one position - in front of vowels - deaf and voiced ones appear, and in others - either only deaf or only voiced. This series of positionally changing consonants form the following voiceless-voiced groups:

| p b | p' -b' | f - in | f’-v’ | t - d | t'-d' |

| \/ | \/ | \/ | \/ | \/ | \/ |

| P 1 | P' 1 | f | f' 1 | T | T' |

| 1 b | 1 b' | in | 1 in' | d | d' |

| From 3 | s’ - s’ | w-f | 1* 1 Ha | k - g | k' - g |

| \/ | \/ | \/ | \/ | \/ | \/ |

| from 1 | from' 1 | sh | sh' | to | to' 1 |

| 1 3 | 1 3’ | well | і | G | 1 G' |

w'

The positional exchange of consonants in the Russian literary language is also associated with the ratio of hard soft consonants before [e]. This means that if both hard and soft consonants are equally combined with vowels [a], [o], [y] (for example, [say] - [m'-ol], [pat] - [n'-at ]th, [bal] - [b'a] z, [fort] - [f'-o] dor, zat[thief] - ko[v'-6r], [that] - [t'b] tya, [dol] - [d'-orn], [sor] - [s'-b] la, [call] - [z'o] rna, [sholk] - [zho] ny, [sh'-o] tka , , [h'-o] lka, egg [tsom], [nbr] s - [gn'-ot], [mouth] - in [r'-o] t, [lo] b - [l'-o ]g, [col] - [k'biln), then in combination with [e], as a rule, only soft consonants appear (for example, * by [ra] - for [r'-a], but for [r 'yo] - for [r'yo]; vi[nom] - ko[n'-om], but vi[n'yo1 - ko[n'yo], se[lu] - ru[l'-u] , but se [l'ё] - ru [l'ё], etc.). With such a positional exchange, an intersecting type of positionally changing hard-soft consonants is also formed, when in some positions - before [a], [o], [y] - both hard and soft consonants appear, and in the other - before [e] - only soft. This type of positionally changing consonants is formed by the following groups of hard-soft consonants:

\/ \/ l' r'

Due to the low prevalence of soft [k '], [g '], [x '] in the Russian literary language, back-lingual ones do not participate in the formation of rows of positionally changing hard-soft consonants.

However, the question of the positional change of hard-soft consonants before [e] is complicated by the fact that in the modern literary language there may not be such a change before this vowel: firstly, before [e] there are hard hissing [w] and [g] and affricate [ts] (for example, [she] st, [zhe] st, [tse] ly), and secondly, and this is the main thing, in widespread borrowed words and abbreviations, in combination with lei, other hard consonants also appear, for example: [peer], [coupe], [back] (football.), [vef] VEF, [mayor], [clfe], bre [tel '], mo [del '], sho [se], cash- [ne], etc. This circumstance leads to the fact that the position before [e] ceases to be one in which only soft consonants can act. Consequently, the syntagmatic law, which dictates the need for a positional change of hard-soft before [e], in the modern ’ language has a limited effect: such a positional change is absolutely subordinate to it only at the junction of morphemes (primarily at the junction of stem and inflection, root and suffix); inside morphemes of the positional exchange of hard-soft before [e] may not be.

Positional changes of consonants in the Russian literary language are associated primarily with the ratio of solid х-м_я гк and х consonants when they are compatible in the flow of speech. Specifically, with the fact that hard consonants, falling into a position before the next soft, are influenced by this consonant and are pronounced softly, however, not all consonants soften before soft consonants, just as similar softening does not occur before any soft consonants: some consonants are more amenable to such softening, others - less, before some consonants, softening is observed more often, before others - less often.

In addition, the softening of consonants before soft consonants in the modern Russian literary language has largely given way to the pronunciation of hard consonants, while in the Old Moscow pronunciation, characteristic of the literary language of the second half of XIX- the beginning of the 20th century, the softening of consonants before soft consonants was much more widespread. So, for example, the norm of the modern literary language is the preservation of the hardness of [r] ptsred with soft labial and soft dental sounds, as well as before [h '] and [w ']: ko [rp '] et, speed [rb '] et, ko[rm '] go, so [rp '] you, in sha [rf '] e, ka [rt '] yna, se [rd '] yy, fo [rs '] yy, ko [rz '] yna, Tuesday,

u.ms [rl '] and, hot [rch '] yets, natu [rSh '] ik, etc. The situation is exactly the same with the pronunciation of the labials before the soft posterior lingual [k ']: in modern "| in the language they are pronounced firmly, whereas earlier they were pronounced softly; cf .: la [pk '] and, la [mkChi, la [fk '] and, gri * Sch 1pk '] Y. SCH;

As for the mitigation of consonants before soft consonants that exists in the modern literary language, it observes sdZh primarily when pronouncing dental [t], [d], [s], [s], [and] before soft ctgmi dental [t '] , [d'], [s'], [h'], [i'], [l'], as well as before [h'] (ІШ'ьд such softening is most often observed in the roots of words: [з'д '] is, vsh ka [s'sChe, [s'n'] eg, ka[z'kChi, after [s'l'] e, kb [z'l'] ik, me[s'tChi, pyo [t'l']i;Sch baint't Chik, o[d'n']y, pyo[n's']ia, be[n'z']in, etc. The same observation I also stand at the junction of the root and the suffix: for (d'nChii, pu [t'n']ik, karma [n'chChik | In Less often, such mitigation is carried out at the junction of consonants [h], "SHCHD kojphh th Suffix -l- : next [z 'l '] next and next [evil '] ive, ha [dtl '] ive and "gaTdlChy, etc.

The softening of consonants before soft ones is also noted at the junction of the prefix and the root, although inconsistently. So, I’m always softly pronounced I to the wrench consonant in prefixes times- (ras-), from- (is-), without- (bes-) / Shch eoz- (vos-), through- (through-) before soft [s 'І, [ЗЇ roots: ra [s's'] ёyat, Щ bChz "zChemelny, chre[s's'] edelnik, without [s's'] ylny, in [s's'] ate and "t Before other soft dental endings, the final consonant of these: "prefixes can be pronounced both softly and firmly: ra[s't'] irat and gt; ra[st'] irat, be[z'd'] tree and be[ zd '] tree, ra [s'l '] chs and ra [evil Chechschshch vo_z'nChyk and vo[zn '] yk Unlike the indicated prefixes, the prefix u lt;¦- before all soft teeth is pronounced softly: d'] eat, I Is'nChimat, [s'l'] live.

In the same way, the preposition is always softly pronounced with the initial soft tooth of the following word: [s'-t'] yomi, [z'-d'] yomi), ";zh '] yimi, [s'- l '] ypoy, [z'-z '] ima, k'-s'] yonom, etc. the consonant is always softly pronounced only before the initial [s '] _ and Щ [з'1 of the root, and before the rest of the soft teeth: іьі.mi; - which the word begins Щ, then softly, then firmly: and [s '-s' You . bёTs '~-s ~' Ієna. ^ beїz '-z "Іemlg F through [s'-count, but: be [s'-t') yourself and be [s-t'] yourself, through [s' -dChen 'and later-[z-dChen, and [s'-nChykh and and [z-nChykh, etc.]

As for the combinations [t] and [d] followed by soft dental attachments of the prefix and the root, then in combination with [t ’] and [dCh] final consonants. prefixes can be pronounced both softly and firmly, depending on which, when a long consonant is formed at the junction of Az, a soft or hard shutter occurs (a pause before opening the organs of speech): o! [d'dChalat and o[tChest, oiddCheat, o[ttChyanut, o[ddChelat. When combined [t], [d] with [sCh,

[ZCH the first ones are pronounced firmly: after [tshon, na[dzchirat, etc.]

The softening of the teeth in front of the soft labials most consistently occurs within the root of the word, cf. z'mChey, [s'vChet, [s'vChinya, [s'p'Iychka, [s'pCheg, [s'mChet.] However, there is also a firm pronunciation of consonants before soft labials.

Prefixes with-, times-(ras-), from-(is-), without-(bes-), through-(through-) before | soft labials are usually pronounced with a soft final consonant: [s'p'] ilyt, [s'v'] return, [s'm']erit, and [z'b'] go, and [z'v '] init, U bg [s'm'] black, deep [s'm'] black, ra [s'v'], etc. On the contrary, prefixes under-, over-, pre-, from- before soft labials in the modern literary language they are pronounced firmly: on [db ']ezhal, on [tp '] to stop [dv '] to tell, about [db '] to, o [tp '] to be. The softening of dental before soft labials at the junction of a preposition and a root is very poorly represented. Basically, in this position, the preposition with is softened: [s’-in’] edrbm, [z’-b’] edby, [s’-m’] yosta. The prepositions from, without, through are often pronounced with a hard dental: and [s-p '] esni, and [s-b '] fir-trees, be [s-v '] yosa, after [s-n '] yon and t d (although, by the way, softening of the tooth at the end of the preposition is also possible). Finally, the prepositions from, over, under, before are pronounced firmly before soft labials: o [t-m '] enya, on [d-m '] yrom, on [t-n '] immbm, on [t-n '] yonoy, re[d-m'] eat.

The softening of labials before soft labials is very rare in modern Russian. In the old Moscow pronunciation, such softening was observed more widely. So, a hard labial is pronounced / n / ed soft at the junction of a preposition and a root: o [b-b '] ereg, o [n-n '] yon; the first consonant is almost always firmly pronounced in the combinations [fm '], [mb '], [mp'1: ri [f-m '] e, bo [mb '] yt, la [mp '] e. The combination [bv '] at the junction of the prefix and the root is pronounced with a hard [b]: o [b '] el, o [b '] yl, But inside the horn - with a soft one: lx) [b '] y. Always softens [m] before [m’1: ha [m’m’] e, su [m’- m’] e; the prefix or preposition v is always softened before [v'], [f'], [m'1: [v'v']el, [f'-f']ylme, [in'm']este, but before [ n '] and [b '] are more often pronounced firmly: [v-b '] eat, [fp '] here, [v-b '] eloi, [f, -n '] esne. \ /

Fluctuations in the softening of consonants before consonants, the difference in the degree of this softening (softness, sometimes semi-softness or preservation / hardness), its instability - all this indicates that: in this phenomenon, it is not the positional change of consonants due to syntagmatic laws, but positional their changes caused by the possible influence of neighboring sounds.

Positional changes also include changes in voiceless affricates [h '] and [c] into voiced [d'zh'] and [dz] and voiceless fricative [x] into voiced fricative [y] at the junction of two words before voiced noisy ones, for example: [doch '] - [dod'zh'-would] daughter would, [lt'ёts] -¦ [lt'edz-would] father would, [bluff] - [pltuu-would] would have gone out. Such positional changes that occur during the continuous pronunciation of two words may not occur if there is at least a slight pause between these words.

Finally, a positional change is the stunning of sonorant consonants at the end of a word after a deaf noisy one and at the beginning of a word before a deaf noisy one: puffy [puffy], loose [puffy], motley [n'sharp], drachm [drachm], yell [yell '], boar [v'ёpr'], mouth [mouth], moss [moss], etc. ~ ~ ~

Positional exchange is perceived and understood by listeners and speakers, as it reflects the laws of the functioning of the phonetic system: violation of these laws means the destruction of the phonetic system of a given language. Positional changes are not perceived and are not realized, since they are not connected with the syntagmatic laws of the phonetic system and therefore may or may not be carried out: for a functioning phonetic system, positional changes are in principle indifferent. The nature of the positional changes of the consonants described above fully confirms this /*?

P o-J positional changes in vowels in the Russian literary language are associated with the impact on them of neighboring - previous uC subsequent - consonants, primarily hard and soft. It| the impact is most clearly detected when the vowels are in the stressed syllable. It is in this position in the literary language! All the vowels that have been described above appear, however / they do not always appear in the same form. In relation to with "-| next consonant, vowels under stress can be in the following.? Eight positions:

- At the absolute beginning of a word before a solid consonant: [th] va, [y] ho, [o] ko, [a] ly V ’

- At the absolute beginning of a word before a soft consonant: [yv '] e, [u-l '] her, and, [al '] little. 'C

- After a solid before a solid consonant: [was], [blew], [peer], f (chorus], [ball]. K

- After hard before soft: [bgl '], [day '], [pe r'i]; [nb-s’it], Shch 1ma-t’]. _4j?

- After soft before soft: [b’il’i], [l’ut’ik], o [l’yos’] e, Ts [t’bt’] I, [m’at’]. i-

- At the absolute end of the word, after the hard one: ra[by], in le[su], .zh shos[se], ki[no], vi[na].

- At the absolute end of the word after the soft: ve [l’y], rotp’y], Щ in ok [n’o], in [s’-o], mo[r’-a]. five,

1 The vowel [s] at the absolute beginning of a word under stress appears only in the pronouns this, such, in the word enny and in interjections eh, eva.

for these vowels, their sound form [a], [o], [y] is the main one, and 1-a] - [a-] - [a], [-o] - [o-] - [b], [ *uZ - [y] - [y] - varieties of the main species. That is why [a], [o], [y] are evaluated as non-front vowels (see § 61): their more and more front varieties, resulting from the influence of neighboring soft consonants, do not appear in Russian in isolated use.

As for the vowels [e] and [i], they are most independent in the position of the absolute beginning of a word before a hard consonant \ in the absolute end of a word after a soft one and in the position after a soft one before a hard consonant. In the same sound characteristic as in these positions, they also appear in isolated use. Neighboring hard consonants have an effect on [e] and [and], informing them of a shift to a more rear formation (cf .: [dz] by - [v-yz] bu, [s'e] in - [se] V) , and if these vowels fall into a position between soft consonants, they become tense, closed. Therefore, for these vowels, their sound form [e], [i] is the main one, and [e] - [e-] - [e] and [s] - [s-] - [i] - varieties of the main form. It is this circumstance that determines the interpretation of [e] and [i] as front vowels (see § 61): more and more back, as well as their tense, closed varieties, resulting from the influence of neighboring hard and soft consonants, do not appear in Russian in isolated use.

In this regard, the vowel [s] is in a somewhat special position, which can be pronounced in an isolated position (and from this point of view, [s] seems to be equated to [e] and [u]), but the absence of this vowel in the absolute beginning of words in Russian, on the one hand, and a clear connection [and] and [s], expressed in the change [and] into [s] after solid consonants (cf .: [ir] a - [k-yr '] e, [and] stbriya - pre[dy] stbriya, etc.), on the other hand, determine the possibility of interpreting [s] as a variety of [and].

The effect of consonants on vowels thus determines the positional changes of vowels in the stressed position. The same positional changes are experienced by vowels in unstressed positions, with the only difference that in unstressed syllables, according to the syntagmatic laws of the Russian literary language, not all and not the same vowels appear as in the stressed position (see below).

Positional changes in stressed vowels in the Russian literary language can be considered quite stable, however, the degree of shifting of non-front vowels into the front zone of formation and the degree of shift of front vowels into the non-front zone or their acquisition of tension and closeness are not the same both for the position of vowels surrounded by consonants of different nature of formation, and and for different native speakers of the literary language.

The positional change of vowels in the Russian literary language depends on their stressed and unstressed positions.

The point is that the Russian language is characterized by

1 Due to the limitation of [e] at the absolute beginning of a word (see above), this position for this vowel should be excluded.

strong stress, in which the vowel of the stressed word differs from the vowels of unstressed syllables in greater tension of articulation, greater longitude and loudness; for example, the vowel [y] in [mind]

more tense, long and loud than [y] in [mind] or in [ugld'it '].

Due to the fact that in a polysyllabic word the stressed vowel is stronger, the vowels of unstressed syllables are weakened and may have a different quality. If we compare Russian stressed and unstressed vowels, it can be established that the vowels [u], [i] and [s] in unstressed syllables become weaker, shorter or pronounced with less articulation tension, but qualitatively they are the same vowels as [u ], [and], [s] under stress, for example: [uh] o - [ear] - [stuck] nose, [yv] a - [needle] - [playful], [cheese] o - [raw ] - [syrl-vat]. Only quantitative weakening is experienced by these vowels in stressed syllables, for example: [water], [kb-n'i], [fish]; [pb-pylu], [krbl'ik'i], [vg v'l-by].

Unlike these sounds, vowels [a], [o], [e] do not appear in unstressed syllables, and in accordance with them, other vowels are pronounced in unstressed positions in the Russian literary language.

In the Russian literary language, there are differences between vowels that appear under stress in the first pre-stressed syllable and in other unstressed syllables. There can be six vowels under stress: [a], [o], [e], [y], [i] (after soft ones) and [s] (after hard ones); in the first pre-stressed syllable, the vowels [y], [i] (after soft ones), [s] (after hard ones), as well as [l] (after hard ones) and [s] (after soft ones) appear; in other unstressed syllables - vowels [y], [i] (after soft ones), [s] (after hard ones), as well as [b] (after hard ones) and [b] (after soft ones).

The vowel [l] is a sound that has the character [a], but is shorter. It is pronounced in the first pre-stressed syllable after solid consonants in accordance with stressed [a] and [o] ([gave] - [dlla], [house] - [dlma]). The vowel [ie] is the sound [and], prone to [e], front row, upper middle rise, non-labialized. It is pronounced in the first pre-stressed syllable after soft consonants in accordance with [a], [o], [e] under stress ([p'at '] - [p'iet'y], [n'-os] - [n 'yesu], [l'esu] - in [l'yesu]). The vowel [ъ] is the so-called reduced (weakened) sound of the back row, mid-upper rise, non-labialized. It is pronounced in unstressed syllables, except for the first pre-stressed, after solid consonants in accordance with [a] and [o] under stress (in the second pre-stressed syllable: [sat] - [sd] ovbd, [water] - [vd] o-vbz ; in stressed syllables: [gave] - [vyd" i], [house] - [na-dm]). The vowel [b] is * a reduced sound, but the front row, middle-upper rise, non-labialized. It is pronounced in unstressed syllables, except for the first pre-stressed, after soft consonants in accordance with stressed [a], [o], [e] in the second pre-stressed syllable: [p'at '] - [n't] a-chbk, [l'- from] - [l'ldkbl, [l'es] - [l'sbvbz; in stressed syllables: [zapr'ych '] - [vypr'k], [v'-ol] - [vyv'l], [ l'es] - [vgl's]).

Therefore, it can be established that in the first pre-stressed syllable in the Russian literary language, non-labialized high vowels [i] and [ы] and labialized [y] and non-high vowels [l] appear after hard and [s] after soft consonants. In the remaining unstressed syllables, the same high vowels appear, as well as non-high vowels [b] after hard and [b] after soft consonants. There is no distinction between middle and low vowels, as is observed under stress, in unstressed syllables: the high vowels are opposed here to a single group of non-high vowels, and in this last group there are no labialized sounds.

The positional exchange of stressed and unstressed vowels is due to the syntagmatic law, according to which in unstressed syllables there can be vowels of only two degrees of rise - upper and non-high, and in the zone of non-high rise - only non-labialized vowels.

It is possible to establish correspondences between stressed and unstressed vowels, but these correspondences only indicate a regular positional change of vowels under stress and without stress, and not about positional changes: this positional change is carried out sequentially, as a reflection of the patterns of functioning of the phonetic system of the Russian literary language.

As a result of such a positional exchange in the Russian literary language, a type of positionally changing stressed and unstressed vowels is formed in parallel with i, when some vowels in different positions retain their quality, while others, differing in one position, are replaced by one vowel of a different quality in other positions. This series of positionally changing vowels can be represented as follows:

Thus, the features of the functioning of the phonetic system of the Russian literary language are primarily associated with the action in it of the syntagmatic laws of the compatibility of sound units, which determine the nature of the positional exchange of consonants and vowels on the syntagmatic axis of the system. The regular positional exchange of consonants and vowels determines the internal connections of sound units in the system, their organization into a single whole.

At the same time, in the phonetic system, as a result of the influence of some sound units on others in the flow of speech, positional changes in sounds develop, which are not determined by syntagmatic laws and therefore do not manifest themselves as consistently as positional

However, both positional change and positional changes determine the specifics of the phonetic system of the modern Russian literary language and the features of its functioning.

Types of phonetic alternations. Phonetic alternations, in turn, are positional and combinatorial. Positional alternation - phonetic alternation of sounds, depending on their position (position) in relation to the beginning or end of the word or in relation to the stressed syllable. The combinatorial alternation of sounds reflects their combinatorial changes due to the influence of neighboring sounds.

Another classification is the division on positional change and positional change. The basic concept for phenomena of phonetic nature is position- phonetically determined place of sound in the flow of speech in relation to significant manifestations of living phonetic laws: in Russian, for example, for vowels - in relation to the stress or hardness / softness of the preceding consonant (in Proto-Slavic - in relation to the subsequent jj, in English - the closeness / openness of the syllable); for consonants, in relation to the end of a word or to the quality of an adjacent consonant. The degree of positional conditioning is what distinguishes the types of phonetic alternations. Positional exchange- alternation, which occurs rigidly in all cases without exception and is significant for semantic discrimination (a native speaker distinguishes it in the flow of speech): “akanye” - indistinguishability of phonemes A and O in unstressed syllables, their coincidence in /\ or in b. Positional change- acts only as a tendency (knows exceptions) and is not recognizable by a native speaker due to the lack of a semantic function: A in MOTHER and MINT are phonetically different A ([[ayaÿ]] and [[dä]]), but we do not recognize this difference; the soft pronunciation of consonants before E is almost mandatory, but unlike I, it has exceptions (TEMP, TENDENCY).

Historical (traditional) alternations are alternations of sounds representing different phonemes, so historical alternations are reflected in writing. Non-phonetic, non-positional (historical) alternations are associated with the expression of grammatical (friend-friends) and derivational (arug friend) meanings: they act as an additional tool for inflection, (form formation and word formation. The historical alternation of sounds that accompanies the formation of derivative words or grammatical forms of words is also called morphological, since it is due to the proximity of phonemes with certain suffixes or inflections: for example, before diminutive suffixes -k(a), -ok etc. regularly alternate posterior lingual with hissing (hand-pen, friend-friend), and before the suffix -yva(~yva-) part of verbs alternate root vowels <о-а>(work out-work out). Types of historical alternations.

1) Actually historical, phonetic-historical- alternations, reflecting the traces of living phonetic processes that once operated (palatalization, the fall of the reduced ones, iotation, etc.);

2)Etymological- reflecting the semantic or stylistic differentiation that once occurred in the language: EQUAL (same) // EQUAL (smooth), SOUL//SOUL; full agreement // disagreement, PRE/PRI.

3) Grammatical, differentiating- having at the synchronic level the function of differentiating grammatical phenomena: NEIGHBOR / / NEIGHBORS (D / / D '') - the change of hard to soft opposes the only and plural(these cases do not include really different indicators, for example, conjugations -I and E, USCH and YASHCH, because here we have before us not changes at the sound level, but the opposition of morphological forms (the same - ENGINEER S//ENGINEER BUT)). It is clear that all these phenomena, which have a different nature, are only conditionally combined into the number of “historical” ones - therefore, the term “non-phonetic” will be more accurate.

LECTURE 8. Positional change and positional changes of vowels and consonants. Historical vowel-consonant alternations

Phonetic processes in the field of vowels .

Positional exchange. The main cases of positional vowel exchange include cases of qualitative reduction of vowels A, O, E in unstressed positions. Qualitative reduction- this is a weakening of the sound, which is accompanied by a change in acoustic-articulation characteristics (the sound changes its DP). There are positions: percussion– the sound remains unchanged (strong position); first pre-shock- the first degree of reduction; second(all other unstressed positions) - the second degree of reduction (weak first and second positions). The sounds I, U, S do not undergo qualitative changes, they change only quantitatively. The qualitative reduction of these sounds has different results, depending on whether they are after a soft or hard consonant. See table.

Let's not forget the manifestation of the absolute beginning of the word, where A and O in both the first and second positions will be the same / \ (instead of / \ for the first and expected b for the second position: [] ORANGE. E, respectively, in the first and second positions will be (instead of the first and Ъ in the second): ETAJERKA [[t/\zh''erk]].

|

first position |

second position |

first position |

second position |

|

*Sometimes after a hard hissing F, W, C in the first position A instead of the expected /\ sounds like E: you just need to remember such words - JACKET, SORRY, SORRY, SORRY, SORRY, RYE, JASMINE, HORSES, TWENTY, THIRTY. But this is no longer for me, but for the next topic (changes), and also for orthoepy.

positional changes. Positional changes include the phenomena accommodation vowels before soft and after soft consonants. Accommodation is the process of mutual adaptation of sounds of different nature (a vowel to a consonant or vice versa). After a soft consonant, a non-front row vowel moves forward and upward in education at the beginning of pronunciation (progressive accommodation), before soft - at the end (regressive accommodation), between soft - throughout pronunciation (progressive-regressive accommodation).

|

MAT - [[MaT MINT - [[M''˙at]] |

MOTHER - [[Ma˙T'']] MOTHER - [[M''däT'']] |

For sounds O, A, E - only under stress - all 4 cases are possible; for sounds U - and under stress, and no all 4 cases; for Ы both under stress and without stress, only 2 cases of Ы and Ыяы are possible, for AND the dot is not put in front, since it is not used after a hard one - 2 cases of И иыы. Sometimes instead of Ё (between soft ones) they denote kê - SING [[n''kêt'']]. Y and JJ are considered soft.

Another case of positional changes is the progressive accommodation of the initial AND in Ы, when a consonant prefix is added to the root: GAME - TO PLAY (this applies to changes, as it knows exceptions - PEDAGOGICAL INSTITUTE may also pronounce AND).

Non-phonetic processes in the region of vowels.

at the root - BIR//BER, GOR//GAR, disagreement//full agreement, E//O, A//I, U//Yu at the beginning of the word, O//E of the SPRING//SPRING type; in the prefix - PRE / / PRI, NOT / / NI, in the suffix - EC / / IK, EC / / IC, OVA / / EVA / / YVA / / IVA, IN / / EN / / AN, in adjectives; at the end - OV / / EV, OY / / HER, OH / / HER, OM / / EM, TH / / OH / / EY

2) Historical phoneme alternations with zero sound (“fluent vowels): at the root - DAY / / DAY, WINDOW / / WINDOWS, COLLECT / / TAKE, WHO / / WHOM, WHAT / / WHAT, in the prefix - THROUGH / / THROUGH, PRE / / PERE, C / / CO, VZ / / WHO , V//VO, OVER//NECESSARY, FROM//OTO, KOY//KOE, in the suffix - PEAS//PEA, RED//RED, BIRD//BIRD, TI//T verbs, SK//ESK, SN//ESN in adjectives, at the end - OY//OYU, in the postfix - СЯ//СЫ

The alternation ONE//ROZ refers to phonetic types of spelling and is one of the rare cases of reflection in writing of not historical, but phonetic alternation within the same phoneme - a strong position O (under stress, which naturally sounds in the first and second positions, respectively, as /\ and Kommersant, which is reflected in the letter as A.

Phonetic processes in the field of consonants.

Positional exchange. The positional less consonants include diverse processes, united by a common feature - they do not know exceptions. 1) Positional stunning of noisy voiced at the end of a word - KIND-GENUS [[T]]; 2) Regressive assimilation by voicing - noisy deaf voiced before voiced MOW-KOSBA [[Z]] (assimilation is the process of assimilation of homogeneous sounds - the influence of vowels on vowels, consonants on consonants, in contrast to accommodation); regressive assimilation in deafness - noisy voiced ones are deafened before noisy deaf ones - BOAT [[T]]. The process does not concern the sonorants - neither the sonorants themselves, nor the noisy ones before the sonorants. The double role of sound B is interesting (it is not by chance that some also consider it sonorous). In front of him, the noisy ones behave not as in front of a voiced, but as in front of a sonorous voice - they do not sound out (TAST: T does not turn into D); and he himself behaves like a noisy voiced - in front of the deaf and at the end of the word is deafened - SHOP [[F]]; 3) Regressive assimilation in softness - will be a change only for the anterior lingual dental D, T, C, Z, N in front of any of them soft: VEST [[C''T'']]; 4) Complete (such assimilation in which the sound changes not only one DP, but completely its entire characteristic) regressive assimilation Z, S before hissing Sh, Zh, Ch, Shch, C - Sew [[SHSH]], HAPPINESS [[SH ' 'W'']]; T and D before H - REPORT [[H''H'']]; T + S \u003d C - FIGHT [[CC]]; T and D before C (FATHERS [[CC]]; C and Z before SH (SPILL [[W''W'']]); 5) Dieresis (loss of sound on a dissimilative basis) - KNOWN, HOLIDAY; 6) Dissimilation ( reverse assimilation - dissimilarity of sounds) G before K - SOFT [[HK]]; 7) Accommodation in softness before I, b, (except C, W, F, H) - HAND / / HANDS [[K]] / / [[K '']]; 8) Vocalization of the phoneme JJ: as a consonant sound jj appears only at the beginning of a stressed syllable (YUG), and in other positions it acts as an AND non-syllable - a vowel sound.

Note: At the end of participial and participle suffixes does not go into F; there is F, because in a strong position it never sounds like B (there is no alternation). The same thing - it is necessary to distinguish, say, the loss of sound in synchrony SUN and in diachrony FEELING, where at the modern level there is no loss, because. there is no alternation with its full variant.

positional changes. Processes that occur as a trend, but with exceptions. 1) Assimilation by the softness of the labial and dental before the labials and P before the labials (Z''VER, LOVE''VI). The old norm required just such a pronunciation, but now, apparently, under the influence of spelling, this is not relevant. 2) Assimilation in softness before jj: most often it softens, but, again under the influence of spelling, before the dividing bj, denoting jj at the junction of the prefix and the root, a solid consonant SEAT [[C]] sounds; 3) Irregular dissimilation of H before T or H: WHAT, OF COURSE [[PC]] [[SHN]] (does not always happen - for example, SOMETHING - only [[TH]]); 4) Accommodation in the softness of hard before E - now, in many foreign words, it is also possible to firmly pronounce the consonant before E: REVENGE [[M '']], but TEMP [[T]]. 5) Stunning of a sonor in position at the end of a word after a hard PETER. 6) Vocalization of a sonor - the acquisition by a sonorant consonant of a syllabic character in a cluster of consonants - KORAB [[b]] L, TEMB [[b]] R. All of these processes are also orthoepic at the same time, because fluctuations in regular pronunciation - this is the reason for orthoepic variation.

Non-phonetic processes in the field of consonants.

1) Historical alternations of phonemes: traces of palatalizations (first, second, third) HAND//HAND; traces of influence of iota LIGHT//CANDLE; traces of simplification of consonant groups BEREGU//BERECH; stun at the end of a word (unchecked DO [[F]]); the historical change of Г to В in the endings of adjectives - RED [[В]]; alternation of suffixes CHIK//SHIK; non-phonetic (phonemic) softness - I WILL // BE, ZARYA // RADIANT (here it is not softening, because in the word ZARYA before A should not be softened (non-front row) - there is no positional conditioning).

2) Historical phoneme alternations with zero sound (“fluent consonants): traces of L-epenteticum - EARTH//EARTH [[–]]//[[L]]; historical diarrhea (untested) FEELING, LADDER; adjective suffixes SK//K; the end of OB (EB) / / - (GRAM / / GRAM).

Note. The change of Z//S in prefixes like IZ, WHO, RAZ, although it is reflected in writing, is in fact not a historical, but a living, phonetic process of assimilation by voiced-deafness: it’s just that phonetic, not phonemic writing is implemented here.

LECTURE 9. Segment and super-segment units. Stress and its types

Linear units are also called segment units, since they are obtained as a result of segmentation against the background of comparison with other similar units as minimal independent fragments. But as a result of the division of the sound stream, other, no longer limiting units are distinguished, which are called supersegmental. Supersegmental units are called units that do not have an independent semantic character, but simply organize the speech flow due to the characteristics of the matter of sound and our organs of speech and senses. If supersegmental units are irrelevant to the expression of meaning, they still have their own articulatory-acoustic specificity. The articulatory-acoustic characteristics of supersegmental units are called PROSODY.

PROSODY - a set of such phonetic features as tone, loudness, tempo, general timbre coloring of speech. Initially, the term "prosody" (Greek prosodia - stress, melody) was applied to poetry and singing and meant some rhythmic and melodic scheme superimposed on a chain of sounds. The understanding of prosody in linguistics is similar to that accepted in the theory of verse in that prosodic features do not refer to segments (sounds, phonemes), but to the so-called supra- (i.e., over-) segmental components of speech, longer in duration than a separate segment, - to a syllable, word, syntagma (intonational-semantic unity, usually consisting of several words) and a sentence. Accordingly, prosodic features are characterized by duration, non-punctuality of their implementation.

Accordingly, the section of phonetics that studies these characteristics is also called. Since their characteristics are reduced to two types of phenomena - STRESS and INTONATION, this section is divided into two subsections: ACCENTOLOGY and INTONOLOGY.

ACCENTOLOGY(Latin akcentus "emphasis" + Greek logos "word, teaching"). 1. The system of accent language means. 2. The doctrine of accent (prosodic) means of language. Aspects of accentology: descriptive, comparative-historical, theoretical. Descriptive accentology explores the phonetic, phonological, grammatical properties of prosodic means. Comparative historical accentology studies the historical changes in accent systems, their external and internal reconstruction. Theoretical accentology describes the systemic relations of prosodic means, the role of meaningful units in the structure, and language functions.

The central concept of accentology is stress.ACCENT in a broad sense –– this is any emphasis (accent) in the flow of sounding speech of one or another of its parts (sound - as part of a syllable, syllable - as part of a word, words - as part of a speech tact, syntagma; syntagma as part of a phrase) using phonetic means. STRESS in the narrow sense - only verbal stress

TYPES OF ACCENTS:

According to the acoustic-articulatory characteristics, monotonic (expiratory) and polytonic (musical, melodic, tonic, tone) stress is distinguished. They also talk about the quantitative type of stress.

The accent of the Russian type has traditionally been considered dynamic, or expiratory. It was assumed that increased respiratory and articulatory effort on stressed vowels is reflected in their increased acoustic intensity.

Another way of organizing the ratio of stressed and unstressed syllables is possible: the vowel of the stressed syllable is lengthened, while the unstressed syllables retain neutral duration (the quality of the vowels almost does not change). These are languages with a quantitative (quantitative) accent. Modern Greek is usually cited as an example of this type of stress. In it, unstressed ones do not undergo reduction and differ from percussion ones only in the absence of an increment in duration. In ancient times, many languages \u200b\u200bhad such an accent.

Traditionally, another type of stress is distinguished - tonal. In Europe, it is represented in South Slavic (Serbo-Croatian and Slovene) and Scandinavian (Swedish and Norwegian) languages. This type of stress is associated with a special interaction of verbal and phrasal prosody. In most languages of the world, the beginning of the tonal movement, which realizes the phrasal accent, is combined with the beginning of the stressed syllable. However, the emergence of two landmarks for placing a tonal accent is also possible. For example, in the Serbo-Croatian language, the stress shifted one syllable to the left (the so-called "retraction"), and at the place of stress, words with a former stress on the second syllable coincided with those that had the initial stress originally; the old orientation of the tonal accent of the phrase was preserved at the same time. Therefore, in words where the stress has not shifted, the falling tone of the statement falls on the stressed vowel, and where it has shifted, the fall of the tone falls on the stressed syllable, and the fall of the tone is often preceded by its rise. As a result, the descending and ascending tones are opposed on the initial stressed syllable. For example, words glory, strength in Serbo-Croatian have a falling accent, and the words leg, needle- ascending.

The emphasis is on the object of selection syllabic, verbal, syntagmatic (clock), phrasal.

stress syllabic- highlighting a certain sound in a syllable. Syllabic stress is a change in the strength of sound or tone of a syllable-forming sound. Usually there are five types of syllable stress: smooth, ascending, descending, ascending-descending, descending-ascending. With ascending stress, the syllable is characterized by ascending intonation. With a downward stress, the stressed syllable is characterized by a descending intonation.

stress verbal- the allocation of one syllable in a word using phonetic means, which serves for phonetic unification. this word.

Russian word stress has qualitative and quantitative characteristics. According to the traditional point of view, Russian word stress is dynamic (power), expiratory, expiratory, i.e. the stressed vowel is the strongest and loudest in a word. However, experimental phonetic studies show that the loudness (“strength”) of a vowel depends both on the quality of the vowel ([a] is the loudest, \y], [and], [s]- the quietest), and from the position of the vowel in the word: the closer to the beginning of the word the vowel is, the greater its volume, for example, in the word gardens an unstressed vowel is stronger than a stressed one. Therefore, an essential characteristic of word stress is its duration: the stressed vowel is longer than the unstressed one. In addition, the stressed syllable is more distinct: under stress, sounds are pronounced that are impossible in an unstressed position.

The languages of the world differ both in the rhythmic schemes allowed in the word, and in the functions performed in them by stress. An example of a language with an exceptional variety of accent (i.e., provided by stress) possibilities is Russian. Since the stress can fall in it on any syllable of the word, it is able to perform a semantic function, opposing pairs of the type: drank - pli, zmok - castle, etc.

In many languages, the stress is fixed, occupying a permanent place in the word. Fixed stress focuses on the extreme positions in the word - either at its beginning or at the end. Thus, Czech and Hungarian have the stress on the first syllable, Polish on the penultimate one, and most Turkic languages on the last one. A close rhythmic organization is found in languages in which the stress can occupy one of two positions oriented to the edge of the word, and its placement depends on the so-called distribution of "light" and "heavy" syllables. "Light" are syllables ending in a short vowel, and "heavy" are syllables that have either a long vowel or a vowel covered by a final consonant. So, in Latin and Arabic, the stress in non-monosyllabic words falls on the penultimate syllable if it is “heavy”, otherwise it shifts to the previous syllable.

Russian stress is not only heterogeneous, but also mobile: it can shift when the grammatical form of the word changes (vod - vdu). English has more limited accent possibilities. As in Russian, the stress in it is different, from which follows the possibility of opposing pairs of the type: ўsubject "subject" -– subўject "to subdue", ўdesert "desert" - deўsert "to desert"; English stress can also change with suffixal word formation: ўsensitive -– sensiўtivity. However, inflectional possibilities in English are small, and there is no change in stress during inflection.

Languages also reveal significant differences in the distribution of gradations of force in the unstressed part of the word. In some languages, all unstressed syllables are equally opposed to stressed syllables, although marginal syllables may have additional amplifications or weakenings. In other languages, the principle of "dipodia" operates: stronger and weaker syllables go through one, with a gradual weakening of strength as they move away from the top. This is the situation in Finnish and Estonian: the main stress in them falls on the first syllable, the secondary stress on the third, and the tertiary stress on the fifth. The situation in Russian is unusual: the pre-stressed syllable here is inferior in strength to the stressed one, but exceeds the others: potakla (here it means reduced a).

There is another possibility of varying the prosodic scheme of a word with "dynamic" stress: different phonetic parameters can reinforce different positions in this scheme. So, in the Turkic languages, the main accent vertex of the word is the final syllable, on which the intonational accent is placed. However, there is also a center of secondary amplification - the initial syllable, which has a loud accent.

Languages without stress (anaccent). In many languages outside of Europe, there is no pronounced accent on the word, and scientists find it difficult to determine the place of stress. A typical example is Georgian, with regard to the rhythmic organization of which there is no single point of view. There is an opinion that the assumption of the obligatory rhythmic association of the syllables of a word is false (V.B. Kasevich and others, S.V. Kodzasov). In his favor speaks, in particular, the history of the Russian language. In Old Russian, a significant number of forms of full-meaning words were the so-called "enclinomena" (V.A. Dybo, A.A. Zaliznyak). These words did not have their own stress and were attached in the form of enclitics to the previous full-stressed words.

Accent functions.Word-forming function: phonetic association of a word. Russian words have only one main (acute) stress, but compound words can have, in addition to the main one, a secondary, secondary (gravitational) stress: cf. rural And agricultural. The word-forming function is also associated with the identification function of word stress, which makes it possible to recognize the word, since the word is characterized by non-two-stress.

One of the most important functions of word stress is differentiating function: stress serves as a means of distinguishing words (flour And flour, castle And Castle) and their different meanings (chaos And chaos), word forms (arms And arms), as well as stylistic variants of the word (calling and unfold call cold and dial. cold, alcohol and prof. alcohol,

Mobile stress is not fixed on a single syllable or morpheme and can be inflectional And derivational. Movable inflectional stress is able to move from one syllable to another during inflection (hand-hands). Movable word-formation stress is able to move from one syllable to another, from one morpheme to another during word formation (horse-horse, hand - pen). Along with the mobile in the Russian language, a fixed stress is also represented: shoe, shoes.

Not every dictionary word has its own verbal stress. Functional words only in exceptional cases receive stress in the flow of speech, but usually they form clitics. In a statement, as a rule, there are fewer stresses than words, due to the formation of phonetic words, in which auxiliary and independent words are combined with one stress.

Accent clock ( syntagmatic) - highlighting one of the words in speech tact(syntagme) by strengthening the word stress, which combines different words into one syntagma. The syntagmatic stress usually falls on the stressed vowel of the last word in the speech tact: There is in the initial autumn / short, / but marvelous time / /.

The speech tact usually coincides with the respiratory group, i.e. a segment of speech uttered by one pressure of exhaled air, without pauses. The integrity of the speech tact as a rhythmic unit is created by its intonational design. The intonation center is concentrated on the stressed syllable of the word as part of the speech tact. - - time accent: On a dry aspen / gray crow/... Each speech measure is formed by one of the intonation structures. The speech beat is sometimes called a syntagma.

The main means of dividing into syntagmas is a pause, which usually appears in combination with the melody of speech, intensity and tempo of speech and can be replaced by sharp changes in the meanings of these prosodic features. One of the words of the syntagma (usually the last one) is characterized by the strongest stress (In logical stress, the main stress can fall on any word of the syntagma).

The phrase usually stands out, contains several speech measures, but the boundaries of the phrase and the measure may coincide: Night. // The outside. // Flashlight. // Pharmacy //(Block). The selection of speech measures can be characterized by variability: cf. Field behind the ravine And Field / behind the ravine.

phrasal stress- highlighting one of the words in a phrase by strengthening the word stress, combining different words into one phrase. Phrasal stress usually falls on the stressed vowel of the last word in the final speech measure (syntagma): There is in the autumn of the original / short, / butwondrousit's time //.

Inside the beat (less often - phrases) there are two types of clock (phrasal) stress, depending on the functions - logical And emphatic.

Stress is logical (semantic)- stress, consisting in highlighting a certain part of a sentence (usually a word), on which the main attention of the speakers is focused. Logical stress is observed in those cases when the content of speech requires a special allocation of some parts of the statement. With the help of logical stress, one or another word is usually singled out in a sentence, which is important from the logical, semantic side, on which all attention should be concentrated

In the flow of speech, the sounds of any language, including Russian, find themselves in a dependent position in relation to each other, while undergoing various modifications due to positional and combinatorial changes.

Positional are called changes in sound, which are due to the place (position) of the sound in the word. Positional changes appear in the form of regular alternations with various conditions implementation of one phoneme. For example, in a series of words pairs - pairs - a steam locomotive, an alternating row is represented by the following sounds: [a] / / / / [b], the appearance of which is explained by qualitative reduction (change in vowel sounds in an unstressed position). The positional process in the area of vowels is reduction, in the area of consonants - the stunning of a voiced double consonant in the position of the end of a word.

Combinatorial changes are called changes in sound, which are due to the interaction of sounds with each other. As a result of such interaction, the articulation of one sound often overlaps with the articulation of another (coarticulation). There are several types of combinatorial changes - accommodation, assimilation, dissimilation, diaeresis, prosthesis, epenthesis, metathesis, haplology, but not all of these processes characterize the literary form of the Russian language. So, for example, metathesis (tubaretka, ralek), prosthesis and epenthesis (kakava, radivo) are more common in vernacular, dialects of folk speech.

Regular changes within the framework of a phonetic word, dictated by the nature of the phonetic position, are called positional exchange (positional alternation).

Sounds in the flow of speech, depending on the position, change qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitative changes lead to the fact that different sounds coincide: for example, the phonemes lt;agt; and lt;ogt; in words, water and vapor are realized in one sound [L]; this type of interleaving is called criss-crossing. Changes that do not lead to the coincidence of different sounds are referred to as parallel types of exchange. For example, changing in an unstressed position, the phonemes lt; and gt; and lt;ygt; however, do not match. N.M. Shansky in his writings adheres to a different understanding of the types of exchange and distinguishes between positional exchange and positional changes.

More on the topic The concept of positional exchange. Types of positional exchange:

- 134. Is an exchange agreement subject to state registration in cases where the object of exchange is real estate?

Social movements and their types

Social movements and their types Yamabushi-ninja teachers and their practices… Yamabushi and the secret of Shugendo numerology

Yamabushi-ninja teachers and their practices… Yamabushi and the secret of Shugendo numerology Secret rite on the Templar coin

Secret rite on the Templar coin How to cook beef heart salad, step by step recipe with photo

How to cook beef heart salad, step by step recipe with photo Carbohydrate-free diet - menu for the week: recipes for weight loss

Carbohydrate-free diet - menu for the week: recipes for weight loss Dynamic gymnastics for newborns

Dynamic gymnastics for newborns Exercises for the press at home

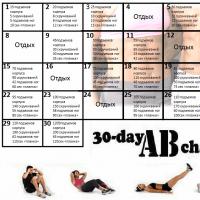

Exercises for the press at home