What is life in history definition. What is life? Characteristic signs of life as a genre

In the literature there is a clear definition of what life is. This is a story about the life and deeds of the leaders of the Christian church, who were awarded the title of saints. Over time, the lives have changed, but the main essence - the glorification of a worthy person, remained in them.

Stories about saints were included in collections and appeared in Russia at the same time as the new religion - Christianity. They immediately fell in love with the circle of literate people and began to be read with great interest.

The task of life

The stories were structured in such a way that the reader could understand why the historical person was called a saint. What is life, it is clear, if you understand what tasks the authors of the writings set for themselves.

The main task of the life - the glorification of the saint, was realized by chanting his courage, courage, ability to cope with difficulties. For example, in the life of Alexander Nevsky, you can read a colorful description of the famous Battle of the Neva, when Alexander rode his horse directly onto the deck of an enemy ship.

The structure of the scriptures

Each life is built according to a single pattern. Be sure to describe information from the history, geography, and sometimes the economy of the place where the saint lived. Therefore, life is a source for historians from which they can draw various information days of the past.

There are cases when ordinary people who have not done anything heroic in their lives were recognized as saints. They were credited with performing miracles that occurred after their death. They also wrote about fictional characters.

Over time, stories about the life of a person were also added to the genre of life, which practically overshadowed the stories about the exploits of the saints. The writers tried to show that the life of a simple person who helps others is no different from the life of martyrs killed in the distant past, and this person deserves due respect.

- (Greek βιος, lat. vita) a genre of church literature that describes the life and deeds of the saints. The life was created after the death of the saint, but not always after formal canonization. Life is characterized by strict content and structural ... ... Wikipedia

Cm … Synonym dictionary

life- life'm life', life'm ... Dictionary of the use of the letter Yo

Life, I, life, in life [not life, eat]; pl. life, uh... Russian word stress

LIFE, I, pl. i, uy, cf. 1. The same as life (in 2 and 3 meanings) (old). Mirnoye 2. In the old days: the narrative genre is a description of life (persons canonized by the church). Lives of the Saints. | adj. life, oh, oh (to 2 meanings). hagiographic literature.… … Explanatory dictionary of Ozhegov

Life, life, life, life, life, life, life, life, life, life, life, life (Source: "Full accentuated paradigm according to A. A. Zaliznyak") ... Forms of words

life- LIFE, i, cf. A text containing a description of the life of a saint, i.e. a church or statesman, martyr or ascetic canonized by the Christian Church, including biographical data, prayers, teachings, etc. Life mentions ... ... Explanatory dictionary of Russian nouns

I cf. 1. The story of the life of a person who is ranked by the church as a saint. 2. Presentation of the most significant facts of life in chronological order; biography. II cf. 1. The time period from birth to death of a person or animal; ... ... Modern explanatory dictionary of the Russian language Efremova

I AM; cf. 1. Biography of what l. saint, ascetic, etc.; their lives and deeds. Lives of the Saints. J. Theodosius of the Caves. 2. Expand. = Life (2, 4 5 digits); life. Carefree Well. ◁ Life, oh, oh (1 character). Zhaya literature. Live tales ... encyclopedic Dictionary

life- a religious and moralistic genre of medieval Christian literature, one of the early forms of applying the biographical method to compiling the biographies of the holy martyrs for the faith, passion-bearers, miracle workers, especially pious, virtuous ... Aesthetics. encyclopedic Dictionary

Books

- The Life of the Great Saint of God, St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, . The life of the great saint of God, saint and wonderworker Nicholas, Archbishop of Myra, taken from the Chetia-Minea on December 6 and May 9, and from the book: Service, life and miracles in the saints of our father ...

- The Life of the Martyrs Grand Duchess Elizabeth and the Nun Varvara, Evil N.. The Life of the Martyrs, compiled by the famous church writer, hagiographer, candidate of historical sciences, Archimandrite Damaskin, known to Orthodox readers as a researcher ...

LIFE, Lives - in Christianity - a genre of church literature, which told about the life of spiritual or secular figures, canonized by the Church as saints. The clerical appointment of Zh. was determined by the strict observance of the basic canons.

Heroes of Zh. are idealized, described in compliance with the basic principles of the genre: a saint is born into a pious family, from childhood he avoids playing with children, prefers prayer and church singing, after the death of his parents he gives all his inheritance to the poor, goes to a monastery, spends time in prayers and patience , performs feats of piety, achieves the love and recognition of the brethren and laity. He is marked by the Holy Spirit (cf. Holy Spirit), he begins to work miracles, speaks with angels and brings many benefits to those who listen and see him, then his death and posthumous miracles are told.

Zh. appeared in the Roman Empire in the first centuries of Christianity (200-209) - during the anti-Christian repressions of Septimius Severus. In the 3-4 centuries. Zh. widely spread in the East, in the Byzantine Empire and Catholic countries Western Europe. Numerous "passions" and martyria told about the martyrdom of those people who, during the persecution of Christians, recognized the one God - Jesus Christ. Many statesmen were also proclaimed saints - kings, princes, emperors, church leaders (founders and abbots [ cm.] monasteries, bishops [ cm.] and metropolitans [ cm.]). Zh. were timed to coincide with a certain date - the day of the death of the saint - and under this number were included in the prologues, menaias, and collections of a stable composition. Usually Zh. were accompanied by church services dedicated to the saint, laudatory words in his honor, and sometimes words for the acquisition of his relics.

In the history of Christianity, there are paintings of martyrs, paintings of holy fathers, in the Western version - martyrology, etc. At the beginning of the 11th century. Byzantine J. Alexei, George the Victorious, Demetrius of Thessalonica, Eustathius Plakida, Andrew the Holy Fool, Euphrosyne of Alexandria, Nicholas of Myra, Simeon the Stylite, Theodore Stratilates, Epiphanius of Cyprus, Kozma and Damian, Mary of Egypt and others through the mediation of Bulgaria were transferred to the lands of the Eastern Slavs . Zh. - martiria - describes in detail the torment to which the saint is subjected before death, trying to force him to renounce his faith. Other J. told about Christians who voluntarily subjected themselves to trials: rich young people secretly left their parents' homes, led a beggarly lifestyle, went into the desert, lived in complete solitude, spent their days in unceasing prayers. A special type of Christian asceticism was pilgrimage - for many years the saint lived in a stone tower (pillar).

The appearance of the original Zh. was connected with the political struggle of Russia for the assertion of its church independence. In 1051, Prince Yaroslav the Wise, consistently striving for the independence of the Russian Church from the tutelage of the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Byzantine emperor, installed Rusyn Hilarion as metropolitan in Kiev and began to insist on the canonization of his brothers Boris and Gleb. A number of monuments are devoted to the life and martyrdom of the princes - a story in The Tale of Bygone Years (1015), "Reading about the life and destruction of the blessed passion-bearer Boris and Gleb" (beginning of the 12th century) by Nestor and the anonymous "Tale and passion and praise of the holy martyr Boris and Gleb" (mid-11th century). In the name of the younger sons of Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich - Boris and Gleb - the idea of tribal seniority in the system of princely hierarchy was consecrated and the tradition of the so-called. princely life in ancient East Slavic literature.

Along with the princely Zh., Zh. began to appear, dedicated to outstanding figures of the Church - the founders of various monastic dormitories. Around 1091, Nestor wrote The Life of Theodosius of the Caves, in which he spoke about an ascetic monk who went to a monastery against the will of his mother, who had a strong and unyielding character. Theodosius overcomes all trials and devotes himself to serving God. In the image of Nestor, Theodosius of the Caves is primarily a stern ascetic - an ascetic, an active owner of the monastery entrusted to him, at the initiative of Theodosius, the monks from the caves finally moved to the Caves Monastery.

"The Life of Theodosius of the Caves" served as a literary source for the Kiev-Pechersk Patericon - a collection of stories about the monks of Kiev Caves monastery. The collection is based on the correspondence of the Bishop of Vladimir-Suzdal Simon with the Kiev monk Polycarp, who lived at the end of the 12th-13th century. The authors portrayed the Saints of the Caves as people of a special type, striving in a relentless struggle to achieve that ascetic ideal that Greek and Eastern monastic communities developed in antiquity. The path of spiritual perfection of the monks is shown against the background of historical reality, many facts are reported that characterize the monastic life of that era, the idea of the glorious past of Kiev and the all-Russian significance of the Caves Monastery and its shrines is affirmed.

Outstanding monuments of Belarusian hagiography of the 12th century. is "The Tale of the Life and Death of Euphrosyne". An unknown author glorifies the persistent ascetic, her desire to achieve knowledge and spiritual perfection. The main character Predslava - the granddaughter of Prince Vseslav, the daughter of Prince Svyatoslav-George - refuses to marry and, against the will of her parents, is tonsured as a nun under the name Euphrosyne (see. Euphrosyne of Polotsk). In the monastery, she rewrites books, writes down prayers and sermons. In the work, literary schematism and didactic rhetoric coexist with the vivid realities of the time, the truthfulness of life descriptions based on real historical facts: the construction of the Transfiguration Church, male and convents, which became the center of culture and education in Polotsk, at her request, Lazar Bogsha created the Cross, where Christian shrines were preserved. The inner world of the heroine is revealed in numerous monologues and dialogues, the work organically combines an artistic description of the life of a saint, short description her travels to Jerusalem and praise.

At the end of the 12th - beginning of the 13th century. a prologue was created by the Bishop of Turov Cyril, in which main character depicted in full accordance with the traditions of the hagiographic literature of the Middle Ages. The son of wealthy parents renounces his inheritance and becomes a submissive monk, spending some time on a pillar. In the final part of Zh., "another Chrysostom is glorified, who in Russia is more than all vosia."

In full accordance with Christian tradition, monk Ephraim wrote The Life of Abraham of Smolensk (beginning of the 13th century), which depicts a talented preacher and an educated monk of the Selishchansky monastery. The author's element plays a significant role in the work. Ephraim reflects, draws analogies with J. Savva and John Chrysostom, uses the stylistic manner of Nestor. The work tells about the persecution of Abraham by the local clergy, who envied his popularity and the love of the people. The author describes the severe physical and mental anguish of the hero, his thorny path to universal recognition.

The period of the struggle against the Mongol-Tatars and the Swedish-German intervention was marked by the writing of princely journals: Alexander Nevsky, Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tverskoy, Mikhail Vsevolodovich Chernigovsky, Dovmont-Timofey, Dmitry Donskoy. In the 1270s-1280s, the scribe of the Vladimir Nativity Monastery wrote The Life of Alexander Nevsky. The author of the work calls himself a contemporary of Alexander, "an eyewitness" of his life and creates a biography of the prince based on his memoirs and the stories of his associates. Starting to describe the "holy, and honest, and glorious" life of the prince, he cites the words of the prophet Isaiah (cf. Yeshayahu) about the sacredness of princely power and inspires the idea of special patronage to Prince Alexander heavenly powers. The acts of the prince are comprehended in comparison with the biblical story, and this gives the biography a special majesty and monumentality. Zh. created the image of a courageous warrior prince, a valiant commander and a wise politician, showing the most significant events from his life - the battle with the Swedes on the Neva, the liberation of Pskov, the Battle on the Ice, diplomatic relations with the Golden Horde and the Pope. Alexander Yaroslavich is the focus of the best qualities of the famous heroes of the Old Testament history - Joseph, Samson, Solomon (see. Shelomo), as well as the Roman king Vespasian. "The Life of Alexander Nevsky" became a model for princely biographies, his influence is felt in "The Tale of Dovmont", in "The Tale of Mamaev massacre", in the "Word on the Life and Repose of the Grand Duke Dmitry Ivanovich Donskoy".

In the 14th - early 15th century. the ideology of a centralized state is being formed, the authority of the grand-ducal power is being strengthened, in literature the moral ideal of a person, purposeful, persistent, capable of self-sacrifice for the good of the people, is brought to the fore. An unknown author created "The Tale of the Life and Repose of the Grand Duke Dmitry Ivanovich, Tsar of Russia", the main character of which is the Moscow prince - the winner of the Mongol-Tatar conquerors, the ideal ruler of the entire Russian land. After the victory of Dmitry Ivanovich over Mamai, "there was silence in the Russian land." At the same time, it is noted that, like David, who had mercy on the children of Saul, Grand Duke was merciful to those who were guilty before him: "forgive the guilty."

An outstanding Russian hagiographer of the first quarter of the 15th century. was Epiphanius the Wise, who wrote "The Life of Stephen of Perm" and "The Life of Sergius of Radonezh" ( cm.- T.K.). The writer sought to show the greatness and beauty of the moral ideal of a person who puts the common cause above all else - the cause of strengthening the Russian state. The "Life of Stephen of Perm" glorifies the missionary activity of a Russian monk who became a bishop in the distant Komi-Permyak land, shows the triumph of Christianity over paganism. "The Life of Sergius of Radonezh" is dedicated to the well-known church and socio-political figure, the founder and abbot of the Trinity Monastery near Moscow. Being well-educated and well-read, Epiphanius the Wise mastered many literary forms and nuances of style, skillfully included biblical quotations and literary reminiscences in his compositions, skillfully used the rhetorically sophisticated style of "weaving words", combining stylistic sophistication with clarity and dynamism of plot development.

In the second half of the 16th century Russian writer and publicist Yermolai-Erasmus created "The Tale of Peter and Fevronia of Murom", in which he tells the love story of a prince and a peasant woman. The author sympathizes with the heroine, admires her intelligence and nobility in the struggle against the boyars and nobles. In each conflict situation, the high human dignity of a peasant woman is opposed to the low, selfish behavior of her noble opponents. The work with extraordinary power glorifies the strength and beauty of female love, which is able to overcome all life's hardships and triumph over death. In the story, there are no descriptions of the pious origin of the heroes, their childhood, feats of piety, characteristic of Zh., the aura of holiness surrounds not ascetic monasticism, but an ideal married life in the world and the wise sovereign control of their principality. After the canonization of Peter and Fevronia at the council of 1547, this work became widespread as J.

In the 17th century genre Zh. is transformed into a household story, these changes are clearly seen in the "Tale of Yuliana Lazorevskaya", written by her son Druzhina Osoryin. The author creates the image of an energetic Russian woman, an exemplary wife and mistress, patiently enduring trials. The story affirms the holiness of the feat of highly moral worldly life and service to people.

Archpriest Avvakum made the next step along the path of Zh.'s rapprochement with reality in his famous Zh.-autobiography. In the 1640s, the question arose of carrying out a church reform, which caused a powerful anti-feudal and anti-government movement - the schism, or Old Believers. The ideologist of the Old Believers was Archpriest Avvakum, who in 1672-1673 created his best creation - "The Life of Archpriest Avvakum, written by himself."

The character of Avvakum is revealed both in terms of family and everyday life, and in his social and political life, the image of a persistent, courageous and uncompromising Russian person is recreated. In denouncing representatives of ecclesiastical and secular authorities, Avvakum does not spare the tsar himself, although he considers the tsar's authority unshakable. The close intertwining of the personal and the social transforms this J. from an autobiographical narrative into a broad picture of the social and socio-political life of his time. In the style of Zh., the skaz form is organically combined with a sermon, which led to the combination of church-bookish elements of the language with dialectal ones. The innovation of Archpriest Avvakum is that he decided to write his own "Zh." and created a brilliant work of the autobiographical genre, which until then had existed in embryonic form in Russian literature. Avvakum directed the main blow of his accusatory criticism against the reforms of Patriarch Nikon. A man of tremendous energy and fortitude, Avvakum showed himself to be a master of polemics and agitation. No tortures and tortures, exiles, persecutions, persuasions of the tsar and boyars, promises of earthly blessings for renouncing his beliefs could force Avvakum to stop fighting against the "heretical whore".

In Orthodoxy, plots from Zh. of the following saints of God are currently very common: John the Baptist; the holy supreme Apostle Peter; holy supreme Apostle Paul; Apostle Andrew the First-Called; Right-Believing Grand Duke Alexander Nevsky (1220-1263); Great Martyr Barbara (3rd - early 4th century, suffered for Jesus Christ c. 306); Equal-to-the-Apostles Grand Duke Vladimir (c. 960-1015); Great Martyr George the Victorious; Great Martyr Catherine (executed between 305 and 313); holy prophet Elijah; Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian; St. John Chrysostom; righteous John Kronstadt (1829-1908); Blessed Xenia of Petersburg (18th - early 19th century); St. Nicholas, Archbishop of the World of Lycia, miracle worker (late 3rd - first half of the 4th century); Equal-to-the-Apostles Grand Duchess Olga (10th century); Great Martyr and Healer Panteleimon (3rd-4th centuries); Reverend Seraphim of Sarov; St. Sergius of Radonezh; forty martyrs of Sebaste (4th century), etc.

T. P. Kazakova

Share:

Life as a genre of literature

Life ( bios(Greek), vita(lat.)) - biographies of saints. The life was created after the death of the saint, but not always after formal canonization. Life is characterized by strict content and structural restrictions (canon, literary etiquette), which greatly distinguishes them from secular biographies. The science of hagiography deals with the study of hagiographies.

More extensive is the literature of the "Lives of the Saints" of the second kind - the saints and others. The oldest collection of such tales is Dorotheus, ep. Tire (†362), - the legend of the 70 apostles. Of the others, the most remarkable are: "Lives of honest monks" by Patriarch Timothy of Alexandria († 385); then follow the collections of Palladius, Lausaik (“Historia Lausaica, s. paradisus de vitis patrum”; the original text is in the edition of Renat Lawrence, “Historia ch r istiana veterum Patrum”, as well as in “Opera Maursii”, Florence,, vol. VIII ; there is also a Russian translation, ); Theodoret of Kirrsky () - “Φιλόθεος ιστορία” (in the named edition of Renat, as well as in the complete works of Theodoret; in Russian translation - in “The Works of the Holy Fathers”, published by the Moscow Spiritual Academy and earlier separately); John Moscha (Λειμωνάριον, in Rosweig's Vitae patrum, Antv., vol. X; Russian ed. - "Lemonar, that is, a flower garden", M.,). In the West, the main writers of this kind in the patriotic period were Rufinus of Aquileia ("Vitae patrum s. historiae eremiticae"); John Cassian ("Collationes patrum in Scythia"); Gregory, Bishop Tursky († 594), who wrote a number of hagiographic works (“Gloria martyrum”, “Gloria confessorum”, “Vitae patrum”), Grigory Dvoeslov (“Dialogi” - Russian translation “Conversation about J. Italian Fathers” in “Orthodox Interlocutor ”; see the research on this by A. Ponomarev, St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg) and others.

From the 9th century in the literature of the "Lives of the Saints" a new feature appeared - a tendentious (moralizing, partly political and social) direction, which adorned the story about the saint with fictions of fantasy. Among such hagiographers, the first place is occupied by Simeon Metaphrastus, a dignitary of the Byzantine court, who lived, one by one, in the 9th, according to others in the 10th or 12th century. He published in 681 "Lives of the Saints", which constitute the most common primary source for subsequent writers of this kind, not only in the East, but also in the West (Jacob Voraginsky, archbishop of Genoa, † - "Legenda aurea sanctorum", and Peter Natalibus, † - "Catalogus Sanctorum"). Subsequent editions take a more critical direction: Bonina Mombricia, Legendarium s. acta sanctorum" (); Aloysia Lippomana, ep. Veronsky, "Vitae sanctorum" (1551-1560); Lawrence Surius, Carthusian of Cologne, "Vitae sanctorum orientis et occidentis" (); George Vizell, "Hagiologium s. de sanctis ecclesiae"; Ambrose Flaccus, "Fastorum sanctorum libri XII"; Renata Lawrence de la Barre - "Historia christiana veterum patrum"; C. Baronia, "Annales ecclesiast."; Rosweida - "Vitae patrum"; Rader, "Viridarium sanctorum ex minaeis graccis" (). Finally, the famous Antwerp Jesuit Bolland comes forward with his activities; in the city he published the 1st volume of the Acta Sanctorum in Antwerp. For 130 years, the Bollandists published 49 volumes containing the Lives of the Saints from January 1 to October 7; two more volumes appeared by the year. In the city, the Bollandist Institute was closed.

Three years later, the enterprise was resumed again, and another new volume. During the conquest of Belgium by the French, the Bollandist monastery was sold, and they themselves moved to Westphalia with their collections, and after the Restoration they published six more volumes. The latter works are significantly inferior in dignity to the works of the first Bollandists, both in terms of the vastness of erudition and due to the lack of strict criticism. Müller's Martyrologium mentioned above is a good abridgement of the Bollandist edition and can serve as a reference book for it. A complete index to this edition was compiled by Potast ("Bibliotheca historia medii aevi", B.,). All the lives of the saints, known with separate titles, are numbered by Fabricius in the Bibliotheca Graeca, Gamb., 1705-1718; second edition Gamb., 1798-1809). Individuals in the West continued to publish the lives of the saints at the same time as the Bollandist corporation. Of these, the following deserve mention: Abbé Commanuel, "Nouvelles vies de saints pour tous le jours" (); Balier, "Vie des saints" (strictly critical work), Arnaud d'Andilly, "Les vies des pè res des déserts d'Orient" (). Among the newest Western editions of the Lives of the Saints, the compositions deserve attention. Stadler and Geim, written in dictionary form: "Heiligen Lexicon", (s.).

A lot of Zh. is found in collections of mixed content, such as prologues, synaksari, menaia, patericons. Prologue name. a book containing the lives of the saints, together with instructions regarding celebrations in their honor. The Greeks called these collections. synaxaries. The oldest of them is an anonymous synaxarion in hand. ep. Porfiry of the Assumption; then follows the synaxarion of Emperor Basil - referring to the X table.; the text of the first part of it was published in the city of Uggel in the VI volume of his "Italia sacra"; the second part was found later by the Bollandists (for its description, see Archbishop Sergius' Monthly Book, I, 216). Other ancient prologues: Petrov - in hand. ep. Porfiry - contains the memory of saints for all days of the year, except for 2-7 and 24-27 days of March; Cleromontansky (otherwise Sigmuntov), almost similar to Petrov, contains the memory of saints for a whole year. Our Russian prologues are alterations of the synaxarion of Emperor Basil with some additions (see Prof. N.I. Petrova “On the origin and composition of the Slavic-Russian printed prologue”, Kiev,). The Menaion are collections of lengthy tales about saints and feasts arranged by months. They are service and Menaion-Chetya: in the first they are important for the biographies of saints, the designation of the names of the authors above the hymns. The handwritten menaias contain more information about the saints than the printed ones (for more details on the meaning of these menaias, see Bishop Sergius' Monthly Books, I, 150).

These "monthly menaias", or service ones, were the first collections of "lives of the saints" that became known in Russia at the very time of its adoption of Christianity and the introduction of worship; they are followed by Greek prologues or synaxari. In the pre-Mongolian period, the Russian Church already had a full circle of menaias, prologues and synaxareas. Then patericons appeared in Russian literature - special collections of the lives of the saints. Translated patericons are known in the manuscripts: Sinai (“Limonar” by Mosch), alphabetic, skete (several types; see the description of the rkp. Undolsky and Tsarsky), Egyptian (Lavsaik Palladia). Based on the model of these eastern patericons in Russia, the “Paterik of Kiev-Pechersk” was compiled, the beginning of which was laid by Simon, ep. Vladimir, and the Kiev-Pechersk monk Polycarp. Finally, the last common source for the lives of the saints of the whole church is calendars and monastics. The beginnings of calendars date back to the earliest times of the church, as can be seen from the biographical information about St. Ignatius († 107), Polycarpe († 167), Cyprian († 258). From the testimony of Asterius of Amasia († 410) it can be seen that in the 4th c. they were so full that they contained names for all the days of the year. Monthly books in the Gospels and the Apostles are divided into three genera: eastern origin, ancient Italian and Sicilian and Slavic. Of the latter, the most ancient is under the Ostromir Gospel (XII century). They are followed by the Mental Words: Assemani with the Glagolitic Gospel, located in the Vatican Library, and Savvin, ed. Sreznevsky in the city. This also includes brief notes about the saints in the church charters of Jerusalem, Studium and Constantinople. The saints are the same calendars, but the details of the story are close to the synaxaries and exist separately from the Gospels and charters.

Old Russian literature of the lives of the saints proper Russian begins with the biographies of individual saints. The model according to which the Russian “lives” were compiled was the Greek lives of the Metaphrast type, that is, they had the task of “praising” the saint, and the lack of information (for example, about the first years of the life of the saints) was made up for by commonplaces and rhetorical rantings. A number of miracles of the saint - necessary component G. In the story about the life itself and the exploits of the saints, there are often no signs of individuality at all. Exceptions from the general character of the original Russian "lives" before the 15th century. constitute (according to Prof. Golubinsky) only the very first Zh., “St. Boris and Gleb" and "Theodosius of the Caves", compiled by Ven. Nestor, J. Leonty of Rostov (which Klyuchevsky refers to the time before the year) and J., who appeared in the Rostov region in the 12th and 13th centuries. , representing an artless simple story, while the equally ancient Zh. of the Smolensk region (“Zh. St. Abraham”, etc.) belong to the Byzantine type of biographies. In the XV century. a number of compilers Zh. begins mitrop. Cyprian, who wrote J. Metrop. Peter (in a new edition) and several Zh. Russian saints who were part of his “Book of Powers” (if this book was really compiled by him).

The biography and activities of the second Russian hagiographer, Pachomiy Logofet, are introduced in detail by the study of prof. Klyuchevsky "Old Russian Lives of the Saints, as a historical source", M.,). He compiled J. and the service of St. Sergius, Zh. and the service of St. Nikon, J. St. Kirill Belozersky, word on the transfer of the relics of St. Peter and service to him; to him, according to Klyuchevsky, belong to J. St. Novgorod archbishops Moses and John; in total, he wrote 10 lives, 6 legends, 18 canons and 4 laudatory words to the saints. Pachomius enjoyed great fame among his contemporaries and posterity and was a model for other compilers of J. No less famous as the compiler of J. Epiphanius the Wise, who first lived in the same monastery with St. Stephen of Perm, and then in the monastery of Sergius, who wrote J. of both of these saints. He knew well the Holy Scriptures, Greek chronographs, palea, letvitsa, patericons. He has even more ornateness than Pachomius. The successors of these three writers introduce a new feature into their works - an autobiographical one, so that one can always recognize the author by the “lives” compiled by them. From urban centers, the work of Russian hagiography passes into the 16th century. in deserts and areas remote from cultural centers in the 16th century. The authors of these Zh. did not limit themselves to the facts of the life of the saint and panegyric to him, but tried to acquaint them with the church, social and state conditions, among which the saint's activity arose and developed. Zh. of this time are, therefore, valuable primary sources of cultural and everyday history Ancient Russia.

The author, who lived in Moscow Russia, can always be distinguished by the trend from the author of the Novgorod, Pskov and Rostov regions. new era in the history of Russians, Zh. is the activity of the All-Russian Metropolitan Macarius. His time was especially plentiful with new "lives" of Russian saints, which is explained, on the one hand, by the intensive activity of this metropolitan in canonizing saints, and on the other hand, by the "great Menaion-Fourths" compiled by him. These Menaia, which included almost all the Russian Zh. available by that time, are known in two editions: the Sophia (manuscript of the St. Petersburg spirit. Acd.) and the more complete - the Moscow Cathedral of the city. the works of I. I. Savvaitov and M. O. Koyalovich, to publish only a few volumes covering the months of September and October. A century later, Macarius, in 1627-1632, the Menaion-Cheti of the monk of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery German Tulupov appeared, and in 1646-1654. - Menaion-Cheti of the priest of Sergiev Posad John Milyutin.

These two collections differ from Makariyev in that they include almost exclusively Zh. and legends about Russian saints. Tulupov entered into his collection everything that he found on the part of Russian hagiography, in its entirety; Milyutin, using the works of Tulupov, reduced and altered the Zh., which he had at hand, omitting prefaces from them, as well as words of praise. What Macarius was for Northern Russia, Moscow, the Kiev-Pechersk archimandrites - Innokenty Gizel and Varlaam Yasinsky - wanted to be for Southern Russia, fulfilling the idea Metropolitan of Kiev Peter Mogila and partly using the materials he collected. But the political unrest of that time prevented this enterprise from being realized. Yasinsky, however, attracted to this case St. Demetrius, later the Metropolitan of Rostov, who, working for 20 years on the revision of Metaphrast, the great Fourth Menaion of Macarius and other benefits, compiled the Chetia Menaion, containing Zh. churches. Patriarch Joachim was distrustful of the work of Demetrius, noticing in it traces of the Catholic teaching on the virginity of the conception of the Mother of God; but the misunderstandings were cleared up, and Demetrius' work was finished.

For the first time, the Menaion of St. Demetrius in 1711-1718 In the city of Synod instructed the Kiev-Pechersk archim. Timothy Shcherbatsky, revision and correction of the work of Demetrius; after the death of Timothy, this assignment was completed by Archim. Joseph Mitkevich and Hierodeacon Nicodemus, and in a corrected form, the Menaion of the Saints were published in the city of Zh. Saints in the Menaion of Demetrius are arranged in calendar order: following the example of Macarius, there are also synaxari for the holidays, instructive words on the events of the life of the saint or the history of the holiday , belonging to the ancient church fathers, and partly compiled by Demetrius himself, historical discussions at the beginning of each quarter of the publication - about the primacy of the month of March in the year, about the indict, about the ancient Hellenic-Roman calendar. The sources used by the author are visible from the list of "teachers, writers, historians" attached before the first and second parts, and from quotes in individual cases (Metaphrastus is most common). Many articles are only a translation of the Greek Zh. or a repetition with correction of the Zh. language of Old Russian. There is also historical criticism in Chetya-Minei, but in general their significance is not scientific, but ecclesiastical: written in artistic Church Slavonic speech, they still constitute a favorite reading for pious people who are looking for in Zh. saints" of religious edification (for a more detailed assessment of the Menaia, see the work of V. Nechaev, corrected by A. V. Gorsky, - "St. Demetrius of Rostov", M., and I. A. Shlyapkin - "St. Demetrius", SPb.,). There are 156 of all individual Zh. ancient Russian saints, included and not included in the counted collections. Demetrius: "Selected Lives of the Saints, summarized according to the guide of the Menaion" (1860-68); A. N. Muravyov, “Lives of the Saints of the Russian Church, also Iberian and Slavic” (); Philaret, archbishop Chernigovsky, "Russian Saints"; "The Historical Dictionary of the Saints of the Russian Church" (1836-60); Protopopov, "Lives of the Saints" (M.,), etc.

More or less independent editions of the Lives of the Saints - Philaret, archbishop. Chernigovsky: a) "Historical Doctrine of the Church Fathers" (, new ed.), b) "Historical Review of Songsingers" (), c) "Saints of the South Slavs" () and d) "St. ascetics of the Eastern Church "(); "Athos Patericon" (1860-63); "High cover over Athos" (); "Ascetics of piety on Mount Sinai" (); I. Krylova, “The Lives of the Holy Apostles and the Legends of the Seventy Disciples of Christ” (M.,); Memorable stories about the life of St. blessed fathers "(translated from Greek,); archim. Ignatius, "Brief Biographies of Russian Saints" (); Iosseliani, "Lives of the Saints of the Georgian Church" (); M. Sabinina, "The Complete Biography of the Georgian Saints" (St. Petersburg, 1871-73).

Especially valuable works for Russian hagiography: Prot. D. Vershinsky, "Months of the Eastern Church" (

biographies of people canonized by the church as saints. Such people were honored with church veneration and commemoration, the compilation of a Zh. was an indispensable condition for canonization, that is, recognition of holiness. Zh.'s clerical appointment was conditioned by the requirement of strict observance of the basic principles of the genre: the hero Zh. had to serve as a model of an ascetic for the glory of the church, to resemble other saints in everything. Composition F was traditional: a story about the childhood of a saint who avoids playing with children, a devout believer, then a story about his life with deeds of piety and miracles performed, a story about death and posthumous miracles. Hagiographers willingly borrow from other magazines both the plot and individual collisions. However, the heroes of Zh. were, as a rule, real people (with the exception of Zh. the first Christian martyrs), and therefore it was in Zh. that, more vividly than in other genres of ancient Russian literature, was also reflected real life. This feature of Zh. was especially strong in the section of miracles that was obligatory for them. Most of the miracles of life are a protocol-business record about the healing of sick and suffering people from the relics of a saint or through prayer to him, about the saint’s help to people in critical situations, but there are many vitally vivid action stories among them. At one time, F.I. Buslaev wrote: “In articles about the miracles of saints, sometimes in remarkably vivid essays, the private life of our ancestors appears, with their habits, sincere thoughts, with their troubles and sufferings” (Buslaev F.I. Historical reader, - M., 1861.-Stb. 736). Oral monastic legends, features of monastic life, the circumstances of the relationship of the monastery with the world, secular authorities, real historical events are reflected in the hagiographic stories about ascetic monks. The life of the founders of monasteries reflect the sometimes very dramatic clashes between the founder of the monastery and the local population. In a number of cases, living human feelings and relationships are hidden behind traditional hagiographic collisions. Very characteristic in this regard is the episode of Zh. Theodosius of the Caves, dedicated to the traditional hagiographic situation - the departure of a young man, the future saint, from home to a monastery. The opposition of the mother of Theodosius to his charitable desire to leave the world and devote himself to the service of God is interpreted by the author as a manifestation of the enemy's will, as a result of devilish instigations, but he describes this situation as a vitally vivid, dramatic picture of maternal feelings. The mother loves her son and rebels against his desire to go to the monastery, but she is a person of a strong, adamant character, and because of her love for her son and the desire to insist on her own, this love turns into cruelty - not having achieved her persuasion and threats, she subjects her son to cruel tortures . Zh. can be divided into several groups according to the type of subjects. Zh.-martiria told about the death of saints who suffered for their adherence to Christianity. These could be the first Christians tortured and executed by the Roman emperors, Christians who suffered in countries and lands where other religions were practiced, who died at the hands of the pagans. In J. martyrias, an almost indispensable plot motif was detailed description torments to which the saint is subjected before death, trying to force him to renounce Christian beliefs. Another group of Zh. narrated about Christians who voluntarily subjected themselves to various kinds of trials: rich young men secretly left their homes and led a half-starved life of beggars, being humiliated and ridiculed; ascetics, leaving cities, went into the desert, lived there all alone (hermits), suffering from deprivation and spending all the days in unceasing prayers. A special type of Christian asceticism was pilgrimage - the saint lived for many years on the top of a stone tower (pillar), in monasteries ascetics could “shut up” in a cell, which they did not leave for an hour until death. Many statesmen were also proclaimed saints - princes, tsars, emperors, church leaders (founders and abbots of monasteries, bishops and metropolitans, patriarchs, famous theologians and preachers). Zh. were timed to coincide with a specific date - the day of the saint's death, and under this number were included in the Prologues, Menaion (collections of lives, arranged in the order of the monthly calendar), in collections of stable composition. As a rule, Zh. was accompanied by church services dedicated to the saint, laudatory words in his honor (and sometimes words for the acquisition of his relics, the transfer of relics to a new church, etc.). Hundreds of Zh. are known in ancient Russian literature, while translated (Byzantine, less often Bulgarian and Serbian) Zh. Orthodox saints, regardless of who they were by nationality and in what country they lived and labored. Of the Byzantine genres, the translations of J. Alexei, the Man of God, Andrew the Holy Fool, Barbara, George the Victorious, Demetrius of Thessalonica, Eustace of Placis, Euthymius the Great, Euphrosyne of Alexandria, Catherine, Epiphanius of Cyprus, John Chrysostom, Cosmas and Damian, Mary of Egypt, Nicholas of Myra, Paraskeva-Friday, Savva the Sanctified, Simeon the Stylite, Theodore Stratilates, Theodore Tiron and other saints. For translations from Greek of some of them, see the book: Polyakova S. V. Byzantine legends.-L., 1972. Zh. Russian saints were created throughout all the centuries of the existence of ancient Russian literature - from the 11th to the 17th centuries. Zh. these can also be systematized according to the type of heroes Zh.: princely Zh., Zh. church hierarchs, Zh. builders of monasteries, Zh. ascetics for the glory of the church and martyrs for the faith, Zh. holy fools. Of course, this classification is very arbitrary and does not have clear boundaries; many princes, for example, appear in Zh. as martyrs for the faith, the founders of monasteries were the most different people and so on. Zh. can be grouped according to the geographical principle - according to the place of life and exploits of the saint and the place of origin of Zh. (Kiev, Novgorod and North Russian, Pskov, Rostov, Moscow, etc.). For the most part, the names of the authors of Zh., as well as in general the written monuments of Ancient Russia, remained unknown to us, but in a number of cases we recognize the names of the writers of Zh from the text of the works themselves, on the basis of indirect data. The most famous Russian authors are Nestor (XI-beginning of the XII century), Epiphanius the Wise (2nd half of the XIV-1st quarter of the XV century), Pachomius Logofet (XV century). Let us list some ancient Russian Zh., grouping them according to the character of the heroes Zh. Zh. ascetics to the glory of the church and the founders of monasteries: Abraham of Rostov, Abraham of Smolensk, Alexander Oshevensky, ALEXANDER SVIRSKY, Anthony of Siya, Varlaam Khutynsky, Dmitry Prilutsky, Dionisy Glushitsky, Zosima and Savvaty Solovetsky, John of Novgorod, Kirill Belozersky, Leonty of Rostov, Pavel Obnorsky, Pafnuty Borovsky, Sergius of Radonezh, Stefan of Perm. Zh. hierarchs of the Russian church - metropolitans: Alexei, Jonah, Cyprian, Peter, Philip. Zh. holy fools: St. Basil the Blessed, John of Ustyug, Isidor of Rostov, Mikhail Klopsky, Procopius of Ustyug. Of the princely Zh., the most famous are: Zh. Alexander Nevsky, Boris and Gleb, Prince Vladimir, Vsevolod-Gavriil of Pskov, DMITRY DONSKOY, Dovmont-Timofey, Mikhail Alexandrovich of Tverskoy, Mikhail Vsevolodovich of Chernigov, Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tverskoy, Feodor, Prince of Smolensk and Yaroslavl. There are few women's women in Russian hagiography: Anna of Kashinskaya, Euphrosyne of Polotsk, Euphrosyne of Suzdal, Juliania Vyazemskaya, Juliania Osoryina (see Osoryin Druzhina), and Princess Olga. Legendary-fairy motifs, local legends sometimes influence the authors of Zh. so strongly that the works created by them can only be attributed to Zh. only because their heroes are recognized by the church as saints and the term “life” may appear in their title, and in terms of their literary nature These are vividly expressed plot-narrative works. This is “The Tale of Peter and Fevronia of Murom” by Yermolai-Erasmus. “The Tale of Peter, Prince of the Orda”, “The Tale of Mercury of Smolensk”. In the 17th century Zh. appear in the Russian North, completely based on local legends about miracles occurring from the remains of people whose life path is not connected with feats for the glory of the church, but is unusual - they are sufferers in life. Artemy Verkolsky - a boy who died from a thunderstorm while working in the field, John and Loggin Yarensky, whether Pomors, roofing felts, monks who died at sea and were found by the inhabitants of Yarenga on ice, Varlaam Keretsky - a priest of the village of Keret, who killed his wife, imposed on himself for this severe test and forgiven by God. All these Zh. are notable for miracles, in which the life of the peasants of the Russian North is colorfully reflected. Many miracles are associated with the deaths of Pomors in the White Sea. For publications of Zh., see the articles in this dictionary: Epiphanius the Wise, Yermolai-Erasmus, Life of Alexander Nevsky, Life of Alexei, the Man of God, Life of Varlaam Khutynsky, Life of Zosima and Savvaty of Solovetsky, Life of Leonty of Rostov, Life of Mikhail Klopsky, Life of Mikhail Tverskoy, The Life of Nicholas of Mirlikiy, The Life of Boris and Gleb, Nestor, Pakhomiy Serb, Prokhor, The Word on the Life of Prince Dmitry Ivanovich, as well as articles about Zh. in the Dictionary of Scribes (see: Issue 1.-S. 129-183, 259-274 ; Issue 2, part l.-C. 237-345; Issue 3, part I-C. 326-394). Lit .: Klyuchevsky Old Russian Lives, BarsukovN P. Sources of Russian hagiography. SPb., 1882, Golubinsky E History of the canonization of saints in the Russian Church - M, 1903, Serebryansky Princely Lives; Adrianov-Peretz V.P.; 1) The tasks of studying the “hagiographic style” of Ancient Russia // TODRL - 1964 - T 20 - C 41-71; 2) Narrative narrative in the hagiographic monuments of the XI-XIII centuries // Origins of Russian fiction. - P. 67-107, Budov n and c I. U. Monasteries in Russia and the struggle of peasants against them in the XIV-XVI centuries ( according to the lives of the saints) - M, 1966; Dmitriev L. A.; 1) Plot narrative in the hagiographic monuments of the XIII-XV centuries. // Origins of Russian fiction. - S. 208-262; 2) Genre of North Russian Lives // TODRL.-1972 - T. 27.- C 181-202; 3) Hagiographic stories of the Russian North as literary monuments of the XIII-XVII centuries: Evolution of the genre of legendary biographical legends. - L., 1973, 4) Literary fate of the genre of ancient Russian hagiographies // Slavic literature / VII International Congress of Slavists. Reports of the Soviet delegation.-M., 1973-S. 400-418, Research materials for the "Dictionary of scribes and bookishness of Ancient Russia". Original and translated lives of Ancient Russia // TODRL -1985 - T 39 - C 185-235; Curds O. V. Old Russian collections of the 12th-14th centuries. Article two Monuments of hagiography // TODRL-1990 T 44.- P. 196-225 L. A. Dmitriev, O. V. Tvorogov

Substances and their physical properties

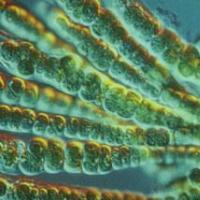

Substances and their physical properties Classification, structure, nutrition and the role of bacteria in nature

Classification, structure, nutrition and the role of bacteria in nature Bacteria - the most ancient organisms on Earth Bacteria - the oldest group of living organisms

Bacteria - the most ancient organisms on Earth Bacteria - the oldest group of living organisms Epithets, metaphors, personifications, comparisons: definitions, examples

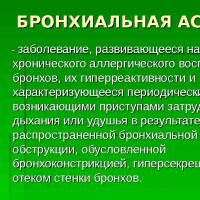

Epithets, metaphors, personifications, comparisons: definitions, examples Bronchial asthma Bronchial asthma

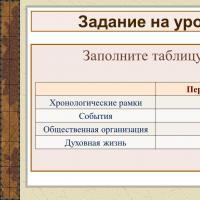

Bronchial asthma Bronchial asthma Roman Empire Ancient History

Roman Empire Ancient History Flexible removable dentures: design, features and benefits Varieties of soft dentures with photos

Flexible removable dentures: design, features and benefits Varieties of soft dentures with photos