Nikolai Aleksandrovich Shchors: biography. Nikolai Shchors - hero of the Civil War: biography

In September 1919, an event took place in Samara that remained almost unnoticed by either the local authorities or the city dwellers. A heavily sealed zinc coffin was unloaded from an ordinary "caravan" of a freight train, which was transported to the All Saints Cemetery, which was located here, near the station. The funeral went quickly, and only a young woman in a mourning dress and several men in mourning stood at the coffin. military uniform. After parting, no sign was left on the grave, and it was soon forgotten about. Only for many years it became known that on that day in Samara they buried the red commander Nikolai Alexandrovich Shchors, who died on August 30, 1919 at the Korosten railway station near Kiev

From the banks of the Dnieper to the Volga

He was born on May 25 (New Style June 6) 1895 in the village of Snovsk (now the city of Shchors) in the Chernihiv region in Ukraine in the family of a railway worker. In 1914, Nikolai Shchors graduated from the military paramedic school in Kiev, and then - military courses in Poltava. He was a participant in the First World War, where he first served as a military paramedic, and then as a second lieutenant on the Southwestern Front.

After the October Revolution, he returned to his homeland, and in February 1918 he created a partisan detachment in Snovsk to fight the German invaders. During 1918-1919, Shchors was in the ranks of the Red Army, where he rose to the rank of division commander. In March 1919, he was for some time the commandant of the city of Kiev.

In the period from March 6 to August 15, 1919, Shchors commanded the First Ukrainian Soviet Division. In the course of a swift offensive, this division recaptured Zhytomyr, Vinnitsa, Zhmerinka from the Petliurists, defeated the main forces of the UNR in the Sarny-Rovno-Brody-Proskurov region, and then in the summer of 1919 defended itself in the Sarny-Novograd-Volynsky-Shepetovka region from the troops of the Polish Republic and the Petliurists , but was forced under pressure from superior forces to withdraw to the east.

After that, on August 15, 1919, during the reorganization of the Ukrainian Soviet divisions into regular units and formations of the unified Red Army, the First Ukrainian Soviet Division under the command of N.A. Shchorsa was merged with the 3rd Border Division under the command of I.N. Oak, becoming the 44th Infantry Division of the Red Army. On August 21, Shchors was appointed head of the division, and Dubovoy was appointed deputy head of the division. It consisted of four brigades.

The division stubbornly defended the Korosten railway junction, which ensured the evacuation of Soviet employees and all supporters of Soviet power from Kiev. At the same time, on August 30, 1919, in a battle with the 7th brigade of the 2nd corps of the Galician army near the village of Beloshitsa (now the village of Shchorsovka, Korostensky district, Zhytomyr region, Ukraine), while in the advanced chains of the Bogunsky regiment, Shchors was killed, and the circumstances of his death remain completely unexplained to this day. At the same time, it came as a surprise to many that the body of the deceased commander was subsequently interred not in Ukraine, where he fought, but very far from the place of his death - in Samara.

Already after the death of Shchors, on August 31, 1919, Kiev was taken by the Volunteer Army of General Denikin. Despite the death of its commander, the 44th Rifle Division of the Red Army at the same time ensured a way out of the encirclement of the Southern Group of the 12th Army. However, the mystery of the death of N.A. Shchorsa has since become the subject of many official and unofficial investigations, as well as the topic of many publications.

eyewitness memories

He spoke about the death of his commander like this:

“The enemy opened heavy machine-gun fire ... When we lay down, Shchors turned his head to me and said:

Vanya, watch how the machine gunner shoots accurately.

After that, Shchors took binoculars and began to look where the machine-gun fire was coming from. But in a moment, the binoculars fell out of Shchors' hands, fell to the ground, and Shchors' head too. I called out to him:

Nicholas!

But he didn't respond. Then I crawled up to him and began to look. I see blood on the back of my head. I took off his cap - the bullet hit the left temple and exited the back of the head. Fifteen minutes later, Shchors, without regaining consciousness, died in my arms.

The same Dubovoy, according to him, carried the body of the commander from the battlefield, after which the dead Shchors was taken somewhere to the rear. The fact that the body of Shchors was soon sent to Samara, Oak, according to all reports, did not even know. And in general, already at that time, the very fact that the burial place of the red commander, who fell in battle in Ukraine, for some reason turned out to be thousands of kilometers from the place of his death, looked very strange. Subsequently, the authorities put forward the official version that this was done in order to avoid possible abuse of the body of Shchors by the Petliurists, who had previously dug up the graves of the Red soldiers more than once, and dumped their remains into latrines.

But now there is no doubt that Samara was chosen for this purpose at the request of the widow of the deceased commander - Fruma Efimovna Khaikina-Shchors

The fact is that it was in this city that her mother and father lived at that time, who could take care of the grave. However, in the hungry year of 1921, both of her parents died. And in 1926, the All Saints cemetery was completely closed, and the grave of Shchors, among others, was razed to the ground.

However, later it turned out that for Samara the legendary red divisional commander was not so much an outsider. As archival materials now open to researchers testify, in the summer of 1918, Shchors, under the surname Timofeev, was sent to the Samara province with the secret task of the Cheka - to organize a partisan movement in the places of deployment of the Czechoslovak troops, who at that time captured the Middle Volga region. However, no details about his activities in the Samara underground have yet been found. After returning from the banks of the Volga, Shchors was assigned to Ukraine, to the post of commander of the 1st Ukrainian Red Division, which he served until the moment of his death.

The hero of the civil war was remembered only two decades later, when Soviet moviegoers saw the feature film Shchors. As is now known, after the directors Vasilyevs released the film Chapaev on the wide screen in 1934, which almost immediately became a Soviet classic, Joseph Stalin recommended that the leaders of Ukraine choose “their Chapaev” from the many heroes of the civil war, so that about him too make a feature film. The choice fell on Shchors, whose career and combat path looked like a model for a red commander. But at the same time, due to the intervention of party censorship in the film "Shchors", which was released on the screen in 1939, little was left of the true biography of the legendary commander

Stalin liked the picture, and after watching it, he asked his entourage a quite reasonable question: how is the memory of the hero immortalized in Ukraine, and what monument is erected on his grave? The Ukrainian leaders clutched their heads: for some reason this circumstance fell out of their field of vision. It was then that the amazing fact came to light that two decades earlier Shchors was buried not in Ukraine, but for some reason in Samara, which by that time had become the city of Kuibyshev. And the saddest thing was the fact that in the city on the Volga there was not only a monument to Shchors, but even traces of his grave. By that time, a cable plant had already been built on the territory of the former All Saints cemetery.

Before the Great Patriotic War the search for the burial place of Shchors was not crowned with success. However, in order to avoid the highest wrath, the regional authorities immediately decided to open a Shchors memorial in Kuibyshev. At the beginning of 1941, a version of the equestrian monument, prepared by Kharkov sculptors L. Muravin and M. Lysenko, received approval. Its laying on the square near the railway station was scheduled for November 7, 1941, but due to the outbreak of war, this plan was never implemented. Only in 1954, an equestrian statue of Shchors, designed by Kharkiv residents, originally intended for Kuibyshev, was installed in Kiev.

Secret expertise

The Kuibyshev authorities returned to the search for the grave of Shchors only in 1949, when, in connection with the 30th anniversary of his death, the regional party committee received a corresponding instruction from Moscow. Here the archivists finally got lucky. According to the surviving documents, they established a direct witness to the funeral of Shchors - the worker Ferapontov. It turned out that in 1919, he, then still a 12-year-old boy, helped a cemetery digger dig a grave for a certain red commander, whose name he did not know. It was Ferapontov who indicated the place where the burial could be located. The worker's memory did not fail: after removing the layer of gravel, a well-preserved zinc coffin appeared to the eyes of the commission members at a depth of one and a half meters. Fruma Efimovna, the widow of Shchors, who was present at the excavations, unequivocally confirmed that the remains of her dead husband were in the coffin.

Based on the results of the exhumation, a forensic medical examination report was drawn up, which for many decades was classified as "Top Secret". In particular, it says the following: “... on the territory of the Kuibyshev cable plant (the former Orthodox cemetery), 3 meters from the right corner of the western facade of the electrical shop, a grave was found in which the body of N.A. was buried in September 1919. Shchors ... After removing the lid of the coffin, the general contours of the head of the corpse were clearly distinguishable with the hair, mustache and beard characteristic of Shchors ... Death of N.A. Shchorsa followed from a through gunshot wound to the occipital and left half of the skull ... The hole in the occiput should be considered the entrance, as evidenced by the oval smooth edges of the bone defect, in the region of the occiput. The hole located in the left parietal region should be considered an exit hole, as indicated by the shape of the hole with a fragment of the outer bone plate ... It can be assumed that the bullet is revolver in diameter ... The shot was fired from back to front, from bottom to top and somewhat from right to left, at close range , presumably 5-10 steps.

From the above text it is clear why the act of the forensic medical examination of the remains of Shchors turned out to be classified for many years. After all, this document completely refutes the official version of the death of Shchors, that he was allegedly hit by a machine-gun burst. Machine guns, as you know, do not fire revolver bullets, and besides, Shchors, looking out of cover, was clearly facing the enemy, and not the back of his head. Consequently, the division commander was shot by someone who was behind him, and not at all by the Petliura machine gunner, as was stated in the canonical memoirs and in the film about the legendary commander. It turns out that in the midst of the battle Shchors removed their own? But if this is so, then who and why did it?

However, eyewitnesses to the exhumation of Shchors' burial in 1949 hardly dared to ask such questions even to themselves. And why? Indeed, after many years of excavations, his grave was nevertheless found, and the day of the mourning ceremony had already been appointed. As a result, the legendary commander was solemnly reburied on July 10, 1949 at the new city cemetery. The ashes of the hero of the civil war were brought here on a gun carriage, and with a large gathering of people, they were buried with all military honors. A memorial marble slab was installed on the grave. A year later, a beautiful granite obelisk with the name of the commander was opened here. At the same time, a bust of the hero was installed at the Kuibyshevkabel plant, where the first grave of Shchors was located. And in 1953, a children's park was opened on the territory of the former All Saints cemetery, which was named after N.A. Shchors. A monument to the legendary Red Divisional Commander was erected in the park

Researchers were able to turn to the question of the true circumstances of the death of Shchors only after the advent of the era of perestroika and glasnost. After 1985, during the declassification of documents from the time of the civil war and the publication of the memoirs of eyewitnesses of the tragedy, almost immediately a version was put forward that Shchors was liquidated on the direct orders of the military people's commissar Lev Davidovich Trotsky

But why did the successful division commander interfere with him so much, and interfered with it to such an extent that the people's commissar did not stop even before his physical elimination?

Apparently, such a reason could be the defiant independence of Shchors, who in many cases refused to follow the orders of his direct leadership, and was also known for striving for the "independence" of Ukraine. A number of memoirs directly state that "Trotsky characterized Shchors as an indomitable partisan, an independent, an opponent of regular principles, an enemy of Soviet power."

It was at this time that, at the suggestion of the military people's commissar Trotsky, a struggle began in the Red Army to strengthen unity of command and tighten discipline, primarily in the execution of orders from higher leadership. The explanation for such a campaign is quite simple. During the civil war, many "independent" armed formations joined the ranks of the Red Army, which were formed around talented self-taught military leaders, nominees from the people's environment. In addition to Nikolai Shchors, Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev, Grigory Ivanovich Kotovsky and Nestor Ivanovich Makhno can be named among them.

But the detachments of the latter, as you know, did not fight for too long in the ranks of the Red troops. Due to constant conflicts with the higher leadership, the Makhnovists quickly broke away from the Bolsheviks, after which they switched to independent tactics of waging war, which often went under the slogan "Beat the Whites until they turn red, beat the Reds until they turn white." But the detachments of Kotovsky, Chapaev and Shchors initially opposed the White Movement. Thanks to the authority of their leaders, they were able to grow to the size of divisions in just a few months, and then they operated quite successfully among other units and formations of the Red Army.

Despite their belonging to the regular units and the oath taken to the Soviet Republic, anarchist tendencies were still quite strong in all the red formations that arose according to the "partisan" principle. This was expressed primarily in the fact that in a number of cases the commanders elected "from below" refused to carry out those orders of the higher army leadership, which, in their opinion, were given without taking into account the situation on the ground or led to the unjustified death of many red soldiers.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the military people's commissar Trotsky, who was constantly reported on all such cases of insubordination, with the consent of the chairman of the Council of People's Commissars Vladimir Lenin, in 1919 launched the above-mentioned campaign in the Red Army to strengthen discipline and "to combat manifestations of anarchism and partisanism." Divisional Commander Nikolai Shchors was on this list of Trotsky among the main "independents" who, in any way, were to be removed from the command staff of the Red Army. And now, in the context of the events of those years and in the light of the foregoing, it is quite realistic to recreate the true picture of the death of divisional commander Shchors, which, like bricks, is made up of individual materials scattered through archives and memoirs.

On that fateful day in August 1919, after a number of orders from the higher army leadership were not followed, a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army, Semyon Ivanovich Aralov, Trotsky's confidant, was sent to Shchors for inspection.

Even earlier, he had twice tried to remove from his post the commander of this "indomitable partisan" and "opponent of the regular troops," as he called Shchors at headquarters, but he was afraid of a revolt by the Red Army. Now, after an inspection trip that lasted no more than three hours, Aralov turned to Trotsky with a convincing request - to find a new division chief, but not from the locals, because "Ukrainians are all as one with kulak sentiments." In a reply cipher, Trotsky ordered him to “carry out a strict purge and refreshment of the commanding staff in the division. A conciliatory policy is unacceptable. Any measures are good, but you need to start from the head.

Head bandaged, blood on the sleeve

In 1989, Rabochaya Gazeta, published in Kiev, reported on exactly what measures were taken to eliminate Shchors. Then she published downright sensational material - excerpts from the memoirs of Major General Sergei Ivanovich Petrikovsky written back in 1962, but then not published for reasons of Soviet censorship

At the end of August 1919, he commanded the Separate Cavalry Brigade of the 44th Army - and, it turns out, also accompanied the division commander to the front line.

As can be seen from the memoirs of Petrikovsky, Comrade Aralov went on a new inspection trip to Shchors not alone, but together with the political inspector of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army, Pavel Samuilovich Tankhil-Tankhilevich (his portrait has not been preserved). Researchers call this person more than mysterious. He was next to Shchors at the time of his death, and immediately after his death he left for the army headquarters. At the same time, in his memoirs, Petrikovsky claims that the shot that killed Shchors rang out after the Red artillery smashed the railway booth, behind which there was an enemy machine gunner, to pieces.

“During the firing of an enemy machine gun,” writes the general, “near Shchors, Dubovoy lay down on one side, and on the other, a political inspector. Who is on the right and who is on the left - I have not yet established, but it no longer matters much. I still think that it was the political inspector who fired, not Dubova...

I think that Dubovoi became an unwitting accomplice, perhaps even believing that this was for the good of the revolution. How many such cases do we know! I knew Dubovoy, and not only from the Civil War. He seemed like an honest man to me. But he also seemed weak-willed to me, without special talents. He was nominated, and he wanted to be nominated. That's why I think he was made an accomplice. And he did not have the courage to prevent the murder.

Bandaged the head of the dead Shchors right there, on the battlefield, personally Oak himself. When the nurse of the Bogunsky regiment, Anna Rosenblum, suggested bandaging more carefully, Dubovoi did not allow her. By order of Dubovoy, the body of Shchors was sent for burial without a medical examination ... Dubovoy could not help but know that the bullet "exit" hole is always larger than the entrance ... ".

Thus, according to all the data, it turns out that Shchors received a revolver bullet in the back of the head precisely from Tankhilevich, and this happened at the moment when he began to look at the location of the Petliura troops through binoculars. It is also clear from the memoirs that Ivan Dubovoi, mentioned above, also became an unwitting witness to this shot, but he hardly wanted the division commander to die - he was then forced to remain silent. And while he was trying to bandage Shchors and pull his body out of the battlefield, Aralov and his assistant, as already mentioned, left the location of the division and went back to headquarters. Subsequently, the traces of the performers were lost somewhere on the fronts, and in 1937 Dubovoy was accused of treason and was soon shot.

For most experts, it seems obvious that Shchors, in the troubled times of the civil war, became one of the many victims of the struggle for power in the Soviet military-political elite. At the same time, historians believe that another red commander, Vasily Chapaev, who for Trotsky was also one of the adherents of "partisanism", could soon share his fate, but just then his "timely" death happened in the waters of the Ural River. And although during the years of perestroika, versions were repeatedly put forward that the death of Chapaev, like Shchors, was set up by Trotsky's inner circle, these assumptions were never found to prove any real evidence.

The mysterious deaths of a number of Red commanders during the civil war and immediately after it are one of the darkest pages of Soviet history, which we are unlikely to ever be able to read to the end. It remains to be hoped that someday this will still be done thanks to the efforts of researchers working with archive materials, which until recently were classified

Valery EROFEEV.

The mystery of the death of the legendary commander N.A. Shchorsa: a look through the years

V last years publications constantly appear in the media, considering the origin of the death of famous people in the recent past: M.V. Frunze, M. Gorky, S.A. Yesenina, V.V. Mayakovsky and others. At the same time, the authors, for the most part, are trying not so much to establish the truth as to present readers with a certain sensation.

The story of the death of Nikolai Aleksandrovich Shchors did not escape similar approaches. Journalists, not bothering to look for opportunities to give a scientific objective assessment of the materials at their disposal, began to assert that Shchors was killed by his own. At the same time, some considered a certain traitor to be the killers of Shchors, others considered the associates of the division commander, whom he somehow did not please. The political inspector of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army P.S. was called the direct perpetrator of the murder. Tankhil-Tankhilevich, an accomplice - Deputy Shchors I.N. Dubovoy2, and the organizer was a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army S.I. Aralov3, who allegedly disoriented L.D. Trotsky in relation to the personality of Shchors. There were also those who considered the direct organizer of the assassination to be the commander of Trotsky himself and regarded it as a counter-revolutionary act4.

The main argument underlying all these versions was the location of the inlet gunshot hole in the occipital region, which is traditionally associated among the townsfolk with a shot in the back of the head. The confessions of Dubovoy, who was repressed in 1937, and the fact that Shchors was buried in Samara, allegedly in order to hide the true reasons for his death and erase the memory of him, were also cited as arguments.

Even a non-specialist understands that in the conditions of hostilities, being in a trench, a person can at some instant be turned to the enemy by any area of the body, including his back. How confessions were obtained in 1937 is also no secret today. From the testimony of F.E. Rostova5 it follows that the decision to bury Shchors' body in Samara was not made by I.N. Dubov, as some authors write about it, and the Revolutionary Military Council of the Army for fear of desecrating his grave, as happened with the grave of brigade commander V.N. Bozhenko6. In favor of the decision to bury in Samara, perhaps, the fact that in May-June 1918, Shchors, on the instructions of the Central Committee of the RCP (b), organized a partisan movement in the Samara and Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk Region) provinces under the name Timofeev. According to some reports, he even participated in the liberation of Samara from the White Czechs. There were other arguments allegedly testifying to the attempt on Shchors (the wound was caused by a revolver bullet, the shot was fired from a parabellum from a distance of 5-10 or 8-10 steps), which, however, when compared with archival documents now stored in the State Archives of Samara regions (GASO) turned out to be untrue7.

Documents related to the study of the remains of N.A. Shchors, from 1949 to 1964 were kept in the archives of the city committee of the CPSU. In September 1964, almost all of them were sent to the Kuibyshev (now Samara) Bureau of Forensic Medical Examination (BSME) to prepare answers to the questions set out in the request of the director of the State Memorial Museum N.A. Shchorsa8. Subsequently, in 1997, the documents sent to the BSME were found in the personal archive of the forensic expert N.Ya. Belyaev, who participated both in the study of the remains of Shchors and in compiling responses to the museum in 1964. In 2003, all documents were submitted to State Archive Samara region. Why the documents were not requested by the archive earlier, we do not know. Another document is “The act of exhumation and medical examination of the remains of the corpse of A.N. Shchorsa" appeared in the GASO in December 1964 after transferring it here from the archive of the CC CPSU. The first of the authors of this article worked for a long time together with N.Ya. Belyaev, and it was to him that archival documents were handed over after the death of N.Ya. Belyaev.

As you know, Nikolai Alexandrovich Shchors, at that time the commander of the 44th Infantry Division, which was part of the 12th Army, died on August 30, 1919 near Korosten, near the village of Beloshitsa, which is 100 km north of Zhytomyr (Ukraine). His body was transported to the city of Klintsy (now the Bryansk region), and the burial took place on September 14, 1919 at the city (formerly All Saints) cemetery in Samara (from 1935 to 1991 - the city of Kuibyshev). Cemetery in 1926-1931 was closed, part of its territory was occupied by a cable factory, and the grave was lost. However, after the war, it became necessary to clarify the cause of the death of the legendary division commander, and they began to look for his burial place. These attempts were crowned with success only in May 1949.

On May 16, 1949, the grave was dug up, but for permission to open the coffin, an appeal was required from the executive committee of the Kuibyshev City Council and the regional committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks to the secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks G.M. Malenkov. On July 5, 1949, at 13:30, the coffin with the remains was removed, taken to the premises at that time of the city forensic medical examination, where on the same day a forensic medical examination was carried out by a commission of 6 people chaired by the head of the city health department K.P. . Vasilyev in order to establish the ownership of the remains of N.A. Shchors. The question of the possible circumstances of the occurrence of a gunshot wound to the skull, identified during the study of the remains, did not arise.

No reports on the activities of the commission were published. The persons who were aware of this also kept silence.

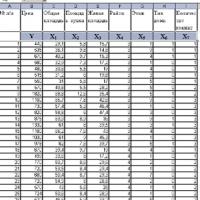

Now, considering the data of both primary and other documents that contain a description of the study of the remains, we have to admit that the study left much to be desired. So, in the study of the skull, the orientation of the length of the hole in the occipital bone was not indicated; the vault of the skull was not separated and the features of damage to the internal bone plate were not studied; the thickness of the skull bones was not measured, especially in the area of damage, which did not meet the requirements of paragraphs. 26, 57 and 58 of the "Rules for the forensic examination of corpses" (1928), which were in force in 19499.

Omitting the details of the study that are not related to the topic of this article, we present a verbatim description of the damage to the bones of the skull presented in the act: “... in the region of the tubercle of the occipital bone, 0.5 cm to the right of it, there is an opening of an irregular oval-oblong shape measuring 1.6 x 0.8 cm with fairly smooth edges. From the upper edge of this hole on the left, slightly rising upwards, through the left temporal bone, there is a crack that does not reach the posterior edge of the left zygomatic bone. In the region of the left parietal bone, on the line connecting the mastoid processes, 5 cm below the sagittal suture, there is a rounded opening 1 x 1 cm with detachment of the outer plate 2 cm in diameter. Fissures extend from this opening in front and downwards to the external auditory opening, forming a closed area of irregular quadrangular shape measuring 6 x 3.5 cm. The distance between the openings in the bones of the skull in a straight line is 14 cm. When the soft tissues of the head were removed, the bone fragments separated, forming hole in the skull.

During the study, photographs were taken of the remains in the coffin and, separately, of the head. The photographs were attached to a document called “Forensic medical opinion”, drawn up by three representatives of the above-mentioned commission: the head of the department of topographic anatomy and operative surgery of the Kuibyshev State Medical Institute (KSMI), doctor of medical sciences, professor I.N. Askalonov; forensic medical experts, assistants of the department of forensic medicine of KSMI N.Ya. Belyaev and V.P. Golubev. All of them are specialists with extensive practical and teaching experience.

This document contains verbatim data from the act on the nature of the damage to the bones of the skull, excluding information about the formation of a hole in the skull after the removal of soft tissues, and ends with conclusions from 5 points.

The first paragraph refers to the cause of death: “The death of Shchors N.A. followed from a penetrating gunshot wound of the occipital and left half of the skull with damage to the substance of the brain, as indicated by the injuries described above on the bones of the skull.

In the second paragraph, in a presumptive form (“apparently”), it refers to the weapon from which Shchors was mortally wounded: “... either from a short-barreled weapon like a revolver or from a combat rifle.” There are no substantiations for this assertion.

In the third paragraph, we are talking about the location of the inlet and outlet holes: “The hole in the occiput should be considered the inlet, as evidenced by the fairly smooth edges of the bone defect in the area of the occiput. The hole, located in the left parietal region, should be considered the exit, as indicated by the shape of the hole with detachment of the outer bone plate.

The fourth point of the conclusions contains an indication of the direction of the shot (“back to front, from bottom to top and somewhat from right to left”) and the area of brain damage - “cerebellum, occipital lobes of the brain and left hemisphere” - “along the bullet channel”.

The first part of this paragraph on the direction of the shot was formulated contrary to the known scientific data on the non-identity of such concepts as the direction of the wound channel and the direction of the shot, since the direction of the gun channel does not always coincide with the external direction of the bullet's flight. Experienced forensic doctors, especially teachers of forensic medicine, could not be unaware of this.

In the last, fifth paragraph, the experts pointed out the impossibility of determining the distance of the shot.

In 1964, on the basis of these documents, a 4-page response was prepared to the director of the State Memorial Museum N.A. Shchors to his requests dated August 6 and September 16, 1964, addressed to the 1st Secretary of the Kuibyshev City Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks L.N. Efremov. The answer was prepared by forensic experts N.Ya. Belyaev and V.P. Golubev, as well as the head of the Kuibyshev BSME N.V. Pichugin.

The preamble of the document says that the director of the museum is sent a "Forensic medical report ..." and photographs of the skull of the deceased. It was also pointed out that it was impossible to determine the caliber of the bullet and the presence of a shell in it, “because when examining the exhumed corpse of Shchors, no special studies were carried out on the shell of the bullet.

The photographs of Shchors' skull are of the greatest value in terms of informativeness, since of all the surviving materials they are the only ones that are not subjective descriptions and opinions, but are an objective reflection of the wound received by Shchors. True, the photographs have a number of significant drawbacks: there is no scale bar or any other object that allows you to determine the scale; the selected angles make it difficult to determine the exact localization of damage. Nevertheless, it was the study of photographs of the Shchors skull that allowed us to take a fresh look at the nature of the gunshot wound, which became fatal. At the same time, the experts' conclusion that there was a gunshot wound on Shchors' skull, as well as conclusions regarding the location of the inlet and outlet holes, did not raise doubts. However, the shape and dimensions of the outlet described in the act, in our opinion, to put it mildly, are incorrect. So, the act states: “After photographing the remains of the corpse in the coffin and separately photographing the head, a medical examination of the head was carried out, and after the separation of the soft covers of the head, along with the hair, the following was found ...”. The photographs show that already during the photographing, part of the bone fragments around the exit hole separated. Most likely, specialists studied and described the skull after their separation. In such cases, to restore the original picture and detailed description you need to re-match the fragments. Perhaps this was not done. In any case, only this, in our opinion, can explain the description of the outlet they presented: "a rounded hole measuring 1 x 1 cm." Fortunately, one of the photographs captured the exit gunshot hole on the skull of Shchors before the separation of the largest fragment.

The photo clearly shows the chips of the outer bone plate along the upper edge, anterior and posterior ends, and along the lower edge at the posterior end, forming a kind of bracket that envelops this part of the defect. These chips characterize the rectangular part of the defect as an exit gunshot injury, and the shape of this part of the defect corresponds to the shape of the bullet profile. In place of the triangular part of the defect, located in the photo in the lower left corner, most likely, there was another fragment (shards), which separated before photographing.

If specialists had described and measured the rectangular part of the defect in the course of the study, this would have allowed them to conclude with a high degree of probability both the alleged projectile and, accordingly, the weapon from which Nikolai Aleksandrovich was mortally wounded.

The absence of a scale bar in the photo, as well as any other large-scale landmarks, makes it impossible for us to draw unambiguous conclusions. However, focusing on the overall dimensions of the skull, as well as on the dimensions of the defects recorded in the act (“a closed area of irregular quadrangular shape with dimensions of 6 x 3.5 cm”, “a rounded hole 1 x 1 cm”), we nevertheless ventured to carry out our own calculations the size of the rectangular area of the bone defect.

According to our calculations, the length of the damage is 3.2 cm, the width at the anterior-lower end is 1.1 cm, the width at the upper-posterior end is 1 cm (the latter size corresponds to the size of the hole specified in the act). Taking into account the direction of the wound channel at the exit, the bullet moved at a fairly acute angle to the parietal bone, so the dimensions of the bone defect are most likely somewhat larger than the dimensions of the bullet profile. But even taking this into account and the possible error in our calculations, the length of the bullet should have been at least 3.0 cm.

Thus, based on the already available data on the nature of the damage to Shchors' skull, supplemented by our calculations, the bullet that mortally wounded Shchors had a diameter of about 0.8 cm (smaller inlet size) and a length of at least 3.0 cm. the bullets known to us, used for firing pistols of that time, do not meet these parameters, first of all, the length.

The most suitable characteristics are the so-called Mannlicher bullet. Its diameter is just 0.8 cm, and its length is about 3.2 cm. The Mannlicher cartridge, as far as we know, was used for firing from the following rifles: Mannlicher Repetiergewehr M.1888 / 90, Mannlicher Repetiergewehr M.1890, Mannlicher Repetier-Karabiner M.90, Mannlicher Repetiergewehr M.1895, Mannlicher Repetier-Karabiner M.1895, Mannlicher Repetier-Stutzen M.1895, as well as for firing from the Schwarzlose MG 07/12 machine gun. All this is a weapon of the so-called strong battle, and it was in the arsenal of the enemy troops10.

A bullet fired from such a weapon has a very high muzzle velocity and therefore kinetic energy. Launched at close range, it would have caused more extensive damage to the skull11.

Due to the high flight speed, the bullet, having formed an inlet in the bones of the skull (after which it may begin to rotate), as a rule, does not have time to turn inside the cranial cavity so much as to leave it with the side surface.

In cases where the bullet enters the cranial cavity in a straight line, without previous rotation, round perforated fractures are usually formed on the skull. Specialists who examined the skull of Shchors explained the elongated shape of the inlet by the fact that "apparently, the bullet did not penetrate into the region of the back of the head of the deceased in a strictly perpendicular direction or was deformed." In our opinion, the most probable version seems to be the ricochet, after which the bullet would inevitably change the direction of flight and could begin to rotate even before entering the skull, and inside the cranial cavity only continue its previously started rotation and exit the side surface. It should also be borne in mind the possibility of a ricochet from an object that was behind the victim. In this case, the shooter had to be located in front and to the side of Shchors.

The data presented indicate that the version of the murder of the legendary commander by his own, especially by anyone who was in his immediate vicinity, in particular Dubov or Tankhil-Tankhilevich, has no real grounds. So the question of who killed Shchors, and whether he was killed intentionally at all or died from a stray bullet from the enemy, remains, in our opinion, still open.

Response to the article [E.A. Gimpelson and E.V. Ponomareva] “Were there any killers?”

In August 2011, an article by Ye.A. and Ponomareva E.V. “Were there any killers? The mystery of the death of the legendary commander N.A. Shchors: a look through the years. Those who are interested in this topic have noticed that the article is a substantially revised version of E.A. Gimpelson’s publication. and Ardashkin A.P. “Intentional murder of N.A. Shchors - truth or fiction?”, Published in the journal Samarskiye Fate, No. 5, 2007.

In both versions, the authors conduct a professional analysis of the results of the exhumation of the remains of N.A. Shchors on the basis of archival materials and photographs of 1949 and convincingly reject the widespread version of the deliberate murder of N.A. Shchors with a shot in the back of the head:

“The data presented indicate that the version of the murder of the legendary commander by his own, especially by anyone who was in his immediate vicinity, in particular Dubov or Tankhil-Tankhilevich, has no real grounds. So the question of who killed Shchors, and whether he was killed intentionally at all or died from a stray bullet from the enemy, remains, in our opinion, still open.

At the same time, the authors express their position, which I fully support, in terms of the assertion that many historical publications do not bother with systematic analysis and try to draw a sensation from fragmentary, unverified facts or simply unfounded statements. Indeed, there are no examples of this.

However, the conclusion that "the version of the murder has no real grounds" seems to me to suffer from the same drawback - the lack of a systematic analysis. But the analysis is not only forensic, but also historical, taking into account all known facts.

First of all, I want to note that the version of deliberate murder was not born from the pen of publicists. She was born among Shchors' colleagues literally the day after his death. But the military and political situation did not allow for an investigation in hot pursuit. And, it is possible that it was precisely this circumstance that prompted Shchors' friends to embalm his body, carefully pack it and bury it far from the army and political leadership. The often stated assertion that the decision to bury Shchors in Samara was made by the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army is not true. According to RVS-12 member Semyon Aralov, the telegram about the death of division commander-44 was received only on September 8, when the funeral train was already on its way to Samara. This is confirmed by the telegram sent after him - immediately return the cool car.

Attempts to initiate an investigation were made in subsequent years. Here is what General Petrikovsky (Petrenko) S.I., a colleague and friend of Shchors, writes in his memoirs:

“If you figure out how the situation developed in the 1st Ukrainian. divisions in the summer of 1919, then the assassination should have happened (followed).

By the way, shortly after the death of the division commander-44, a purge of command personnel was carried out in the division, under which Petrikovsky himself fell under, being the commander of the Special Cavalry Brigade. (But he was soon picked up by Frunze and appointed military commissar of the 25th Chapaev division).

And much later, the former member of the RVS-12, Semyon Aralov, spoke in his memoirs:

“... It should be added that, as it turned out then from a conversation over a direct wire from the beginning. Headquarters of the 1st division, Comrade Kasser, Shchors did not inform the units of the division of the plan for their withdrawal and left the Zhitomir-Kiev highway, which is extremely important for the defense of Kiev, open to the enemy, which was regarded as a failure to comply with the combat order.

I think it is not worth reminding readers what this phrase means during the period of hostilities.

Attempts to understand the ridiculous death of Nikolai Shchors were made in subsequent years. But the deeper the veterans penetrated into history, the more terrible the conclusions loomed - the involvement of influential party officials. And the veterans come to the decision that it is not worth further promoting the topic of the murder of Nikolai Shchors, “... since such a version discredits our party. And they poured so much shit on us.”

Let me also remind you of the well-known confession of Ivan Dubovoy, made by him in 1937 in the dungeons of the NKVD. Ivan Dubovoy, quite unexpectedly and of his own free will, wrote a statement in which he confessed to the murder of Shchors, committed by him for selfish reasons, being Shchors' deputy. But the authorities did not bother with this fact - Dubovoy was still threatened with a "tower" for anti-Soviet activities. The question is: why did Dubovy need to invent this story, if earlier in his memoirs he claimed - "the bullet entered the temple and exited the back of the head." And Dubovoy was the only real witness to the death of Shchors - "he died in my arms." Or, as they say, "there is no smoke without fire"?

For the first time, the murder of Shchors was widely voiced by “his own” writer Dmitry Petrovsky in 1947 in his book “The Tale of the Regiments of Bogunsky and Tarashchansky”:

“No one has yet seen, except for Bogengard, that the bullet that killed Shchors entered his neck - below the ear and went into the temple, that she pierced him - treacherous - from behind. That the killer, like a snake, gets confused and sews between the ranks of those striving for revenge. [cit. according to the 1947 edition]

It should be noted that many veterans immediately condemned this book and demanded that it be withdrawn from circulation. The motive is the same - no one can defame the party.

I draw your attention to the fact that everything mentioned above refers to the period before 1949, i.e. before the results of the exhumation appear, the version of a planned murder should not be attributed to an invention of publicists based on the 1949 Exhumation Act.

And in 1962, veterans, historians and party organs were blown up by a letter from S.I. Petrikovsky:

“... I am writing this letter not for publication. I do not consider it useful now to correct in print what has already been written. But in any Soviet or party court, I undertake to prove that Ivan Dubovoi is an accomplice in the murder or murderer of Nikolai Shchors. My present letter is my witness statement…”.

In 1964, Petrikovsky could not be pulled out of the third heart attack. And the party organs by force extinguished all discussions on this score. Some materials of the investigation into the death of Shchors fell into the hands of publicists only in the late eighties. And it smelled strongly of fried food.

Now directly to the article. I am not an expert in the field of forensics and I was impressed by the informative and convincing analysis carried out by the authors of the article. But I still don't get it:

Or they believe that the experts of 1949 (I emphasize, it was 1949, not 1964) had some kind of external influence that forced them to “slightly” dissemble.

In fact, there are two expert opinions. One was made in 1949 on real remains, and the second, made in 1964 from photographs and archival documents. Moreover, the conclusion of 1949 contains uncompromising statements (with the exception of the type of weapon "revolver-rifle" and the distance of the shot), while the answers of experts in 1964 are for the most part vague and probabilistic. It is possible that this was due to the fact that in 1964 the experts had to answer direct and fairly professional questions, and they understood that something important, and not just idle curiosity, depended on their answer. One thing was not in doubt - the inlet at the back of the head, and the outlet at the temple.

Now to the question of rebound. Of course, the version of the authors of the article contains convincing evidence and has every right to exist, although it is probabilistic. But in this case, the legal competence of the experts of both 1949 and 1964 is questionable. After all, if the experts considered the option of a ricochet, then the Act would have had a legally clear wording: "The bullet entered the back of the head and exited the temple," and not an unequivocal statement: "The shot was fired from behind." Those. not just a bullet entered from behind, but a shot was fired from behind, which calls into question the version of the rebound. It seems like the experts had no doubts about this.

And in conclusion, a few words about the fundamental foundations of the discussion. Some researchers, and I agree with them, suggest that all this controversy - who fired, from what weapon, from where, etc. - this is an attempt to divert the question from the main thing: is Shchors' death purposeful and does it fit into the formula "no person - no problem." Including acts of exhumation are only indirect evidence.

1 Shchors Nikolai Aleksandrovich (May 25 (June 6), 1895, Snovsk village, now Shchors, Chernihiv region, Ukraine - August 30, 1919, Beloshitsa village, now Shchorsovka village, Zhytomyr region, Ukraine). He graduated from the military paramedic school (1914) and military school (1916). Member of the First World War, second lieutenant (1917). In the Red Army since 1918, he organized a partisan detachment that fought against the German invaders. In May-June 1918, he organized the partisan movement in the Samara and Simbirsk provinces, in September, in the Unechi region, he formed the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Regiment named after. Bohun. From November 1918 - commander of the 2nd brigade of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division, which liberated Chernigov, Fastov, Kiev. From February 1919 - commandant of Kiev, from March - head of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division, which liberated Zhytomyr, Vinnitsa, Zhmerinka from the Petliurists, defeated their main forces in the area of Sarny, Rovno, Radzivilov, Brody, Proskurov, staunchly defended in the area Novograd-Volynsky, Shepetovka, Sarny. Since August 1919, he commanded the 44th Infantry Division, which stubbornly defended the Korosten railway junction, which ensured the evacuation of Soviet institutions from Kiev and the exit from the encirclement of the Southern Group 12 A. He was awarded the Honorary Weapon by the Provisional Workers 'and Peasants' Government of Ukraine.

2 The argument about Dubovoy's involvement in the murder of Shchors was based on the opinion prevailing at that time about the constant difference in the magnitude of the entry and exit wounds. Dubovoi, according to his accusers, knew about this, saw the wound, but wrote that the bullet entered from the front and exited from behind (See: N. Zenkovich. Bullet from a livorvert // Rural youth. 1992. No. 1. P. 52-57) ; Ivanov V. Who shot the division commander? // Interfax Vremya--Samara and Samara newspaper of September 5, 2001; Erofeev V. The mystery of the death of Shchors // Volga commune. No. 234. 2009. July 4.

3 Aralov Semyon Ivanovich (1880-1969). In the revolutionary social democratic movement since 1903, a member of the CPSU (b) since 1918. During the Civil War - a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic, the army, the South-Western Front. In 1921-1925. - Plenipotentiary in Lithuania, Turkey, then worked in the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, the Supreme Council of the National Economy.

4 See: Petrovsky D.V. The Tale of the Regiments of Bogunsky and Tarashchansky. M., 1955. S. 398, 399.

5 See: “Testimony of Rostova Fruma Efimovna, wife of N.A. Shchors, living [at that time]: Moscow, 72, st. Serafimovicha, 2, apt. 487, tel.: 31-92-49. The document is on two pages, at the end of it the date and place of compilation are indicated: “May 7, 1949, Kuibyshev” and Rostova’s signature. State Archive of the Samara Region (GASO). F. 651. Op. 5. D. 115.

6 Bozhenko Vasily Nazarevich (1871-1919) - hero civil war, member of the Bolshevik Party since 1917, in 1918-1919. - a participant in the battles with the German interventionists and Petliurists in Ukraine. In 1918-1919. - commander of the Tarashchansky partisan regiment, then the Tarashchansky brigade in the 1st Ukrainian (44th) division N.A. Shchors. Parts of Bozhenko took part in the liberation of the territory of Soviet Ukraine from the German interventionists, Hetmans and Petliurites. See also: Shpachkov V. The paramedic who became the red commander // Medical newspaper. No. 70. 2007. 19 Sept.

In the Soviet Union, his name was a legend. Streets and state farms, ships and military formations were named in his honor. Every schoolboy knew the heroic song about how “the commander of the regiment walked under the red banner, his head was tied, blood on his sleeve, a bloody trail spreads over damp grass.” This commander was the famous hero of the Civil War, Nikolai Shchors. In the biography of this man, whom I. Stalin called the "Ukrainian Chapaev", there are quite a few "blank spots" - after all, he even died under very strange and mysterious circumstances. This mystery, which has not been revealed so far, is almost a hundred years old.

In the history of the Civil War 1918-1921. there were many iconic, charismatic figures, especially in the camp of the "winners": Chapaev, Budyonny, Kotovsky, Lazo ... This list can be continued, no doubt including the name of the legendary Red Divisional Commander Nikolai Shchors. It is about him that poems and songs were written, a huge historiography was created, and the famous feature film by A. Dovzhenko “Shchors” was shot 60 years ago. There are monuments to Shchors in Kiev, which he courageously defended, Samara, where he organized the partisan movement, Zhitomir, where he smashed the enemies of the Soviet regime, and near Korosten, where his life was cut short. Although a lot has been written and said about the legendary commander, the history of his life is full of mysteries and contradictions, over which historians have been struggling for decades. The biggest secret in the biography of the division chief N. Shchors is connected with his death. According to official documents, the former lieutenant of the tsarist army, and then the legendary red commander of the 44th Infantry Division, Nikolai Shchors, died from an enemy bullet in the battle near Korosten on August 30, 1919. However, there are other versions of what happened ...

Nikolai Shchors, a native of Snovsk Gorodnyanskosh district, in his short life, and he lived only 24 years, managed a lot - he graduated from a military paramedic school in Kiev, took part in the First World War (after graduating from the cadet school evacuated from Vilna in Poltava, Shchors was sent to the South-Western Front as a junior company commander), where, after difficult months of trench life, he developed tuberculosis. During 1918-1919. the former ensign of the tsarist army made a dizzying career - from one of the commanders of the small Semenovsky Red Guard detachment to the commander of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division (from March 6, 1919). During this time, he managed to be the commander of the 1st regular Ukrainian regiment of the Red Army named after I. Bohun, the commander of the 2nd brigade of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division, the commander of the 44th rifle division and even the military commandant of Kiev.

In August 1919, the 44th Streltsy Division of Shchors (the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Division joined it), which was part of the 12th Army, held positions at a strategically important railway junction in the city of Korosten west of Kiev. From last strength the fighters tried to stop the Petliurists, who at all costs tried to take over the city. When on August 10, as a result of a raid by the Don Cavalry Corps under General Mamontov, the Cossacks broke through the Southern Front and set off towards Moscow along its rear, the 14th Army, which had taken the main blow, began to hastily retreat. Between the whites and the reds, now only the Shchors division, which was fairly battered in battles, remained. However, the fact that Kiev could not be defended was clear to everyone, it was considered only a matter of time. The Reds had to hold out in order to evacuate institutions, organize and cover the retreat of the 12th Army of the Southern Front. Nikolai Shchors and his fighters managed to do it. But they paid a high price for it.

On August 30, 1919, divisional commander N. Shchors arrived at the location of the Bogunsky brigade near the village of Beloshitsa (now Shchorsovka) near Korosten and died on the same day from a mortal wound to the head. The official version of the death of N. Shchors was as follows: during the battle, the divisional commander watched the Petliurists from binoculars, while listening to the reports of the commanders. His fighters went on the attack, but suddenly an enemy machine gun came to life on the flank, the burst of which pressed the Red Guards to the ground. At this moment, the binoculars fell out of the hands of Shchors; he was mortally wounded and died 15 minutes later in the arms of his deputy. Witnesses of the mortal wound confirmed the heroic version of the death of the beloved commander. However, from them, in an unofficial setting, there was also a version that the bullet was fired by one of their own. To whom was it beneficial?

In that last battle, there were only two people in the trench next to Shchors - assistant commander I. Dubova and another rather mysterious person - a certain P. Tankhil-Tankhilevich, a political inspector from the headquarters of the 12th Army. Major General S.I. Petrikovsky (Petrenko), who at that time commanded the 44th cavalry brigade of the division, although he was nearby, ran up to Shchors when he was already dead and his head was bandaged. Dubovoy claimed that the division commander was killed by an enemy machine gunner. However, it is surprising that immediately after the death of Shchors, his deputy ordered the dead head to be bandaged and forbade the nurse, who ran from a nearby trench, to unbandage it. It is also interesting that the political inspector lying on the right side of Shchors was armed with a Browning. In his memoirs, published in 1962, S. Petrikovsky (Petrenko) cited Dubovoy's words that during the skirmish, Tankhil-Tankhilevich, contrary to common sense, shot at the enemy from a Browning. One way or another, but after the death of Shchors, no one else saw the staff inspector, traces of him were already lost in the first days of September 1919. It is interesting that he also got to the front line of the 44th division under unclear circumstances by order of S.I. Aralov, a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army, as well as the head of the intelligence department of the Field Headquarters of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic. Tankhil-Tankhilevich was a confidant of Semyon Aralov, who hated Shchors "for being too independent." In his memoirs, Aralov wrote: "Unfortunately, persistence in personal conversion led him (Shchors) to an untimely death." With his intractable character, excessive independence, and recalcitrance, Shchors interfered with Aralov, who was a direct protege of Leon Trotsky and therefore was endowed with unlimited powers.

There is also an assumption that Shchors' personal assistant I. Dubova was accomplices in the crime. General S.I. Petrikovsky insisted on this, to whom he wrote in his memoirs: “I still think that the political inspector fired, and not Dubova. But without the assistance of Dubovoy, the murder could not have happened ... Only relying on the assistance of the authorities in the person of Deputy Shchors Dubovoy, on the support of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army, the criminal [Tankhil-Tankhilevich] committed this terrorist act ... I knew Dubovoy not only from the Civil War. He seemed like an honest man to me. But he also seemed weak-willed to me, without special talents. He was nominated, and he wanted to be nominated. That's why I think he was made an accomplice. And he did not have the courage to prevent the murder.”

Some researchers argue that the order to liquidate Shchors was given by the people's commissar and head of the Revolutionary Military Council L. Trotsky, who liked to purge among the commanders of the Red Army. The version associated with Aralov and Trotsky is considered by historians to be quite probable and, moreover, consistent with the traditional perception of Trotsky as an evil genius. October revolution.

According to another assumption, the death of N. Shchors was also beneficial to the "revolutionary sailor" Pavel Dybenko, a more than well-known personality. The husband of Alexandra Kollontai, an old party member and friend of Lenin, Dybenko, who at one time held the post of head of the Central Balt, provided the Bolsheviks with detachments of sailors at the right time. Lenin remembered and appreciated this. Dybenko, who had no education and was not distinguished by special organizational skills, was constantly promoted to the most responsible government posts and military posts. He, with invariable success, failed the case wherever he appeared. First, he missed P. Krasnov and other generals, who, having gone to the Don, raised the Cossacks and created a white army. Then, commanding a sailor detachment, he surrendered Narva to the Germans, after which he not only lost his position, but also lost his party card. Failures continued to haunt the former Baltic sailor. In 1919, while holding the post of commander of the Crimean army, the local people's commissar for military and naval affairs, as well as the head of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Crimean Republic, Dybenko surrendered Crimea to the Whites. Soon, however, he led the defense of Kiev, which he mediocrely failed and fled the city, leaving Shchors and his fighters to their fate. Returning to his possible role in the murder of Shchors, it should be noted that as a person who came out of poverty and managed to get a taste of power, Dybenko was terrified of another failure. The loss of Kiev could be the beginning of his end. And the only person who knew the truth about how Dybenko “successfully” defended Kiev was Shchors, whose words could be heeded. He knew all the ups and downs of these battles thoroughly and, moreover, had authority. Therefore, the version that Shchors was killed on the orders of Dybenko does not seem so incredible.

But this is not the end. There is another version of the death of Shchors, which, however, hardly casts doubt on all the previous ones. According to her, Shchors was shot by his own guard out of jealousy. But in the collection "The Legendary Commanding Officer", published in September 1935, in the memoirs of Shchors's widow, Fruma Khaikina-Rostova, the fourth version of his death is given. Khaikina writes that her husband died in battle with the White Poles, but does not provide any details.

But the most incredible assumption, which is associated with the name of the legendary divisional commander, was expressed on the pages of the Moscow weekly Sovremennik, which was popular during the “perestroika and glasnost” period. An article published in 1991 in one of his issues was truly sensational! It followed from it that the divisional commander Nikolai Shchors did not exist at all. The life and death of the red commander is supposedly another Bolshevik myth. And its origin began with the well-known meeting of I. Stalin with artists in March 1935. It was then that the head of state allegedly turned to A. Dovzhenko with the question: “Why do the Russian people have the hero Chapaev and a film about the hero, but the Ukrainian people do not have such a hero?” Dovzhenko, of course, instantly understood the hint and immediately set to work on the film. As the heroes, according to Sovremennik, they appointed the unknown Red Army soldier Nikolai Shchors. In fairness, it should be noted that the meeting of the Soviet leadership with cultural and art workers in 1935 really took place. And it was precisely from 1935 that the all-Union glory of Nikolai Shchors began to actively grow. The Pravda newspaper in March 1935 wrote about this: “When the director A.P. Dovzhenko was awarded the Order of Lenin at a meeting of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and he returned to his place, he was overtaken by the remark of Comrade Stalin: “You have a debt - Ukrainian Chapaev“. Some time later, at the same meeting, Comrade Stalin asked Comrade Dovzhenko questions: “Do you know Shchors?” “Yes,” Dovzhenko replied. "Think about him," said Comrade Stalin. There is, however, another - absolutely incredible - version, which was born in "near-cinema" circles. Until now, the legend roams the corridors of GITIS (now RATI) that Dovzhenko began filming his heroic revolutionary film not at all about Shchors, but about V. Primakov, even before the arrest of the latter in 1937 in the case of the military conspiracy of Marshal Tukhachevsky. Primakov was the commander of the Kharkov Military District and was a member of the party and state elite of Soviet Ukraine and the USSR. However, when the investigation into the Tukhachevsky case began, A. Dovzhenko began to re-shoot the movie - now about Shchors, who by no means could be involved in conspiratorial plans against Stalin for obvious reasons.

When the Civil War ended and memoirs of participants in the military and political struggle in Ukraine began to be published, the name of N. Shchors was always mentioned in these stories, but not among the main figures of the era. These places were reserved for V. Antonov-Ovseenko as the organizer and commander of the Ukrainian Soviet armed forces and then the Red Army in Ukraine; Commander V. Primakov, who proposed the idea of creating and commanded units and formations of the Ukrainian "Red Cossacks" - the first military formation of the Council of People's Commissars of Ukraine; S. Kosior, a high party leader who led the partisan movement in the rear of the Petliurists and Denikinists. All of them in the 1930s. were prominent party members, held high government positions, represented the USSR in the international arena. But during the Stalinist repressions of the late 1930s. these people were ruthlessly exterminated. About who I. Stalin decided to fill the empty niche of the main characters of the struggle for Soviet power and the creation of the Red Army in Ukraine, the country learned in 1939, when the Dovzhenko film “Shchors” was released. The very next day after its premiere, the performer leading role E. Samoilov woke up popularly famous. At the same time, no less fame and official recognition came to Shchors, who had died twenty years earlier. Such a hero as Shchors, young, brave in battle and fearlessly killed by an enemy bullet, successfully “fitted” into the new format of history. However, now the ideologists face a strange problem, when there is a hero who died in battle, but there is no grave. For official canonization, the authorities ordered to urgently find the burial of Nikolai Shchors, which no one has remembered so far.

It is known that in early September 1919, the body of Shchors was taken to the rear - to Samara. But only 30 years later, in 1949, the only witness to the rather strange funeral of the divisional commander was found. It turned out to be a certain Ferapontov, who, as a homeless boy, helped the caretaker of the old cemetery. He told how late in the autumn evening a freight train arrived in Samara, from which they unloaded a sealed zinc coffin, which was very rare at that time. Under the cover of darkness, keeping secrecy, the coffin was brought to the cemetery. After a short “funeral meeting”, a three-time revolver salute sounded and the grave was hastily covered with earth, setting up a wooden tombstone. The city authorities did not know about this event and no one looked after the grave. Now, after 30 years, Ferapontov led the commission to the burial place ... on the territory of the Kuibyshev cable plant. Shchors' grave was found under a half-meter layer of gravel. When the hermetically sealed coffin was opened and the remains were exhumed, medical commission, who conducted the examination, concluded that "the bullet entered the back of the head and exited through the left parietal bone." “It can be assumed that the bullet was revolver in diameter ... The shot was fired at close range,” the conclusion wrote. Thus, the version of the death of Nikolai Shchors from a revolver shot fired from a distance of only a few steps was confirmed. After a thorough study, the ashes of N. Shchors were reburied in another cemetery and finally a monument was erected. The reburial was carried out at a high government level. Of course, materials about this were kept for many years in the archives of the NKVD, and then the KGB under the heading "Secret", they were made public only after the collapse of the USSR.

Like many commanders of the Civil War, Nikolai Shchors was only a "bargaining chip" in the hands of the mighty of the world this. He died at the hands of those for whom their own ambitions and political goals were more important than human lives. These people did not care that, left without a commander, the division had practically lost its combat effectiveness. As the hero of the Civil War and a former member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Ukrainian Front E. Shadenko said, “only enemies could tear Shchors away from the division, into whose consciousness he had grown roots. And they tore it off."

V. M. Sklyarenko, I. A. Rudycheva, V. V. Syadro. 50 famous mysteries of the history of the XX century

August 30 marks the 95th anniversary of the death of the great red commander Nikolai Shchors. Pyotr Wrangel, one of the main leaders white movement, wrote about such people: “This type had to find his element in the conditions of real Russian unrest. During this turmoil, he could not but be at least temporarily thrown onto the crest of a wave, and with the cessation of the turmoil, he also inevitably had to disappear.

And really, what would our hero expect in a peaceful life? Paramedic career? Doctor? Unlikely. He, the son of a wealthy peasant (according to other documents - an employee of the railway), and in the First world war was an ordinary military paramedic. True, then he became an officer. And in 1917 he received the rank of second lieutenant. But it's time for trouble...

The rise of Shchors falls precisely at a time of anarchy and madness. The time of charismatics, for only bright personalities could curb and ride the muddy stream of the revolution. And there were plenty of these among the Reds, and among the Whites, and among the peasant rebels. Semyon Budyonny and Grigory Kotovsky, Andrei Shkuro and Roman Ungern-Sternberg, Nestor Makhno and brothers Alexander and Dmitry Antonov.

Exactly 150 years ago, on August 25, 1859, Imam Shamil, blockaded in the village of Gunib, surrendered to the governor of the Caucasus, Prince Baryatinsky. This capitulation became the decisive moment of the Caucasian War and predetermined its favorable outcome for Russia. It was the longest war in history Russian Empire.

Naturally, legends arose around a bright personality, the circumstances of life (or death) attracted attention and gave rise to speculation. And it is no longer the son of a peasant, Vasily Blucher, who successfully fights against Kolchak and Wrangel (and receives the Order of the Red Banner No. 1), but a German general in the Bolshevik service. And Kolchak buries a treasure somewhere, almost the entire gold reserve of the Russian Empire. And Shchors turns out to be a colonel in the tsarist army (by the way, this legend is played up in the Soviet film Shchors, in which Yevgeny Samoilov played the title role). And they allegedly killed him...

Stop. With the origin and rank of the red field commander, we somehow figured it out. We only add that Shchors received his primary education at a parochial school. That is, either he himself, or, rather, his parents saw him clothed with a spiritual title. But he didn’t want to heal souls - he wanted to heal bodies, and then not so much to heal, but to cripple physically (field commander) and spiritually (Bolshevism) ...

Let's talk about his death.

According to the official Soviet version, on August 30, 1919, the commander of the 44th Infantry Division, Nikolai Shchors, died in battle with the Petliurists while defending the strategically important Korosten railway junction. The stubborn defense of the station ensured the successful evacuation of Kiev and the exit from the encirclement of the so-called Southern Group of the 12th Red Army.

Almost simultaneously, several alternative hypotheses emerged. One of them was connected with the allegedly tense relations between Shchors and the then head of the military department of the young Soviet republic, Lev Trotsky. There are two arguments. Firstly, Shchors was a typical field commander, or, as they said then, a partisan, and Lev Davidovich oh how he did not like such irregular formations, trying to create a professional professional army. That is why Trotsky had more than tense relations with such fans of partisanism as Semyon Budyonny or Vasily Chapaev. Secondly, not far from Shchors at the time of his death was a certain Pavel Tankhil-Tankhilevich, a political inspector, a man of Sergei Aralov, the godfather of the GRU (then the intelligence department of the field headquarters of the Revolutionary Military Council). Aralov hated Shchors and bombarded his chief Trotsky with alarm notes, not without reason drawing attention to the low discipline and relative combat effectiveness of the division entrusted to Shchors. Could Tankhil-Tankhilevich shoot Shchors? Theoretically it could. But why?

Why would the all-powerful Trotsky kill an ordinary division commander from around the corner? If by no means all-powerful at that time, Budyonny and Voroshilov successfully achieved the arrest and execution of the real creator of the legendary first cavalry army, Boris Dumenko, but he was no less popular than Shchors, and had more weight - the commander of the cavalry corps. It was easier to blame Shchors for the surrender of Kiev, since the city, despite the desperate defense, was doomed, and fell the day after the death of Nikolai Alexandrovich. Moreover, a public trial and execution are always disciplined. And this was well known to the architect of the institute of detachments and revolutionary tribunals, Leon Trotsky.

In the 1920s and 1930s it was fashionable to give large cities the names of Soviet leaders. So, in 1926, in order to honor the memory of Ilyich, the city of Simbirsk, in which he was born, was renamed Ulyanovsk. V different time Soviet cities were named after Sverdlov, Kemerovo, Kalinin, Molotov, Brezhnev, Ordzhonikidze and, of course, Stalin. After all, until 1925 the current city of Volgograd was Tsaritsyn (by the way, there is a metro station in Prague, which is still called "Stalingrad"). In addition to Stalingrad, the city of Stalinsk, which we all know under the name of Novokuznetsk, was also dedicated to the leader of the peoples. Thus, the Bolsheviks apparently tried to get away from everything that would remind of the monarchy: in 1920 Ekaterinodar was renamed Krasnodar, in 1926 Nikolaevsk became Novosibirsk. Some historians believe that in the era when the country was just rising from the hell of the Civil War, there was no better way propaganda of communist ideas than this one.

And, despite the denunciations of Aralov, Trotsky treated Shchors quite positively. Shortly before his death, he was appointed commander of the 44th division. But if he was not pleased with him, he could either lower his rank or remove him from positions of power.

Another version is "literary". It was proposed by the writer, friend of Pasternak and Khlebnikov Dmitry Petrovsky in the book "The Tale of the Regiments of Bogunsky and Tarashchansky". (These regiments were part of the Shchors division, and the division commander himself fell at the location of the Bogunsky regiment.) By the way, Petrovsky himself is a veteran of the Civil War. He also fought in Ukraine. The version is connected with elementary envy. The 44th division was made up of a bunch of broken units. There are two candidates for division commanders: Nikolai Shchors and Ivan Dubovoi. But one division will lead, and the second will obey him until better times. Nikolai Alexandrovich headed. Ivan Naumovich obeyed. Could Ivan Dubovoy hold a grudge, especially if at one time he was the head of Shchors (when he commanded the revolutionary 1st Ukrainian Army)? Theoretically it could. But he didn't hold back.

The fact is that such mergers and resubmissions were a common place (especially considering that the small White armies managed to defeat the Bolsheviks almost until the last day of the struggle). And they obeyed strict rules to exclude such grievances. The consolidated unit was headed by the commander who at the time of the merger had more bayonets. Shchors had more of them. Dubovoy complied. It is interesting that when Petrovsky published his book in 1947, Shchors' colleagues, who knew about the condemnation of the NKVD Dubovoy (in the case of Yakir), did not believe the accusation.

It turns out that the official version turned out to be correct, except that Shchors successfully lost the campaign near Kiev. And not only…

In the Soviet years, in addition to the already mentioned film, the “Song of Shchors” by Matvey Blanter and Mikhail Golodny was still popular. It seems that her words, addressed to the fighters of Shchors, are “Boys, whose will you be, / Who leads you into battle?” - are quite symbolic: really, who and for whom leads them to fight? The Whites, at least, were for Russia.

Youth

Born and raised in the village of Korzhovka, Velikoschimelsky volost, Gorodnyansky district, Chernihiv province (since 1924 - Snovsk, now the regional center of Shchors, Chernihiv region of Ukraine). Born into the family of a wealthy peasant landowner (according to another version - from the family of a railway worker).

In 1914 he graduated from the military paramedic school in Kiev. At the end of the year, the Russian Empire entered the First World War. Nikolai went to the front first as a military paramedic.

In 1916, the 21-year-old Shchors was sent to a four-month accelerated course at the Vilna Military School, which by that time had been evacuated to Poltava. Then a junior officer on the Southwestern Front. As part of the 335th Anapa Infantry Regiment of the 84th Infantry Division of the Southwestern Front, Shchors spent almost three years. During the war, Nikolai fell ill with tuberculosis, and on December 30, 1917 (after the October Revolution of 1917), Lieutenant Shchors was released from military service due to illness and went to his native farm.

Civil War

In February 1918, in Korzhovka, Shchors created a Red Guard partisan detachment, in March - April he commanded a united detachment of the Novozybkovsky district, which, as part of the 1st revolutionary army, participated in battles with German invaders.

In September 1918, in the Unecha region, he formed the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Regiment named after P.I. Bohun. In October - November, he commanded the Bogunsky regiment in battles with German interventionists and hetmans, from November 1918 - the 2nd brigade of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division (Bogunsky and Tarashchansky regiments), which captured Chernigov, Kiev and Fastov, repelling them from the troops of the Ukrainian directory .

On February 5, 1919, he was appointed commandant of Kiev and, by decision of the Provisional Workers' and Peasants' Government of Ukraine, was awarded an honorary weapon.